“How Beaver Stole Fire from the Pines”

Culture: Nimíipuu (Nez Percé) | Narrator: James Reubens | Source: Packard (1891:327)

Entry by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Story

Once, before there were any people in the world, the different animals and trees lived and moved about and talked together just like human beings. At this time the pine-trees had the secret of fire, and guarded it jealously from the rest of the world, so that, no matter how cold it was, nobody could get any fire to warm himself by, unless he was a pine. At length an unusually cold season came, and all the animals were in danger of freezing to death because they could get no fire; but all plans to find out their secret from the pines were in vain, until Beaver hit upon one which proved successful.

At a certain place on Grande Ronde River, in Idaho, the pines were about to hold a great council. They had built a large fire at which to warm themselves, after coming out of the icy water from bathing, and had posted sentinels round about to keep off all the animals and other intruders, who might steal their fire secret.

But Beaver had hidden under the bank near the fire before the sentinels had been posted, and so escaped their notice. After a while, a live coal rolled down the bank close by Beaver, which he seized and hid in his breast, and then ran away as fast as he could. The pines immediately raised the hue and cry, and started after him. Whenever he was hard pressed, Beaver darted from side to side, and dodged his pursuers, and when he had a good start he kept a straight course. Hence the Grande Ronde River is very tortuous in some parts of its course and then straight for some distance, because it preserves the direction Beaver took in his flight.

After running a long time, the pines grew tired and decided to abandon the chase. So most of them halted in a body on the river banks, where they remain in great numbers to this day, and form a growth so dense that hunters can hardly get through it. A few, however, kept on after Beaver, but they finally gave out one after another, and they also remain scattered at intervals along the banks of the river in the places where they stopped.

There was one cedar running with the foremost pines, and although he despaired of capturing Beaver, he said to the few pines still in the chase, “Although we cannot catch Beaver, I will keep on to the top of the hill yonder, and see how far he is ahead.” So he ran to the top of the hill, and saw Beaver far ahead, just diving into Big Snake River where the Grande Ronde enters it, so that further pursuit was out of the question. He saw Beaver dart across Big Snake River and give fire to some willows on the opposite bank, and recross farther on and give fire to the birches, and so on to certain other kinds of wood. Since then, all who have wanted fire have got it from these particular woods, because they have fire in them and give it up more readily than other kinds when rubbed together in the ancient way.

Cedar still stands all alone on the very top of the hill where he stopped in the chase after Beaver, near the junction of the Grande Ronde and Big Snake rivers. He is very old; so old that his top is dead, but he still stands as proof of the truth of the story. That the chase was a very long one is shown by there being no cedars within a hundred miles upstream from where he stands. The old people point him out to the children as they pass by, and say, “See, there is old Cedar standing in the very spot where he stopped chasing Beaver.”

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Zoology

This story contains information about beaver behavior and habitat. It tells us that beavers live along rivers, particularly where willow, birch, and pine grow, and that they hide under river banks. It also identifies two specific rivers (or their tributaries) where beaver can be found–the Grande Ronde and the Snake. Although not explicitly stated, the references to willow, birch, and pine imply that these trees are important to beavers in some way–perhaps for food or for building dams. Because Beaver is sometimes on land and sometimes in the water, the story indicates that beavers are both terrestrial and aquatic. When Cedar sees Beaver dive into the Snake River and cross to the other side, this tells us that beavers are strong swimmers. The description of Beaver’s flight suggests that beavers dart from side to side when closely pursued by predators, but travel in a straight line when they have a good lead.

This information is useful for locating, tracking, and hunting beaver. The information about beaver habitat tells hunters where to look for beaver or signs of their presence (such as tracks, dams, or gnawed branches). The information that beavers dart from side to side could be useful for tracking and pursuing them. The information that beavers swim indicates that they can escape a hunter by diving into the water, which suggests that trapping might be a more effective way of catching them than hunting.

Beaver | Photo by McGill Library on Unsplash

Beaver | Photo by Šárka Krňávková on Unsplash

Snake River | Photo by David Young on Unsplash

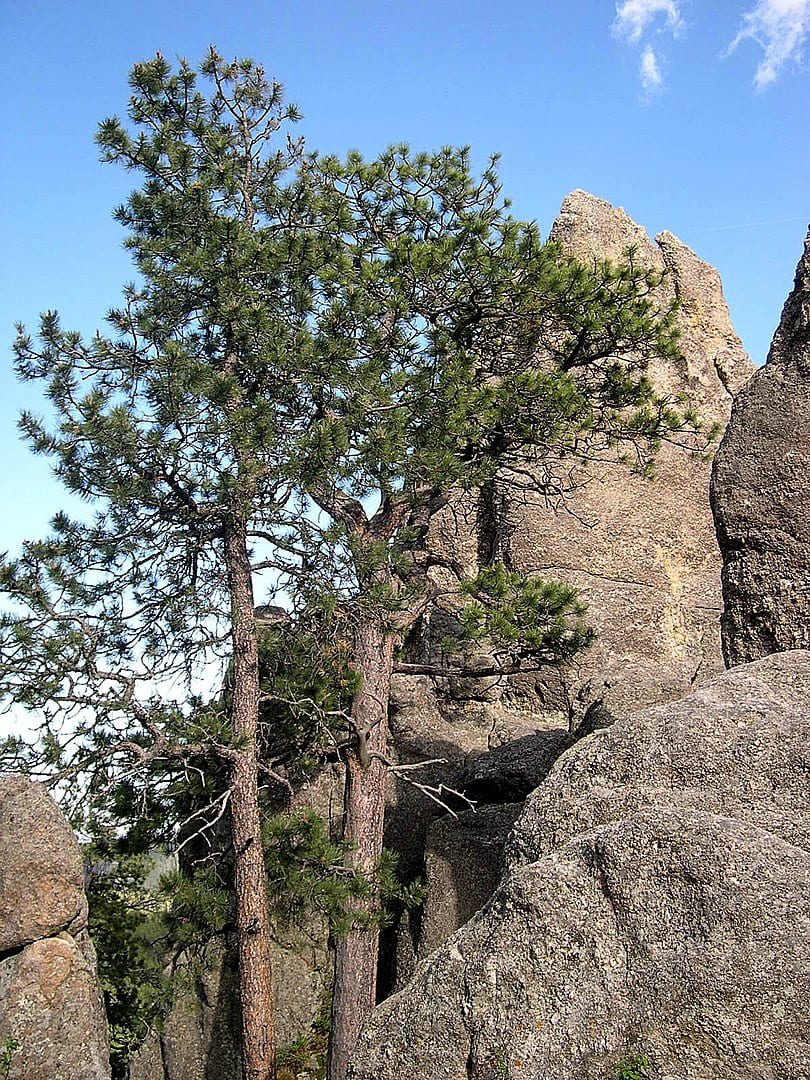

Ponderosa pine | Photo by Jason Sturner

Cedar | Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Willow | Salix lucida lasiandra

Birch | Photo by Donald Giannatti on Unsplash

Botany

This story identifies four types of wood that ignite readily and are good for making fire: pine, cedar, willow, and birch. It also provides information about the growth habits of pine: these trees can grow in stands so dense that people can barely travel through them, but can also grow in a more scattered formation. The story also references the habitat of these species: pine, willow, and birch grow near rivers, while cedar grows on hilltops. More specifically, the story indicates that pine is found in abundance along the Grande Ronde River, that willow and birch are found on either side of the Grande Ronde at its junction with the Snake, and that there is no cedar for a hundred miles upstream of this junction.

This information is useful for making a friction fire: some types of wood are difficult to ignite using this technique, so knowing what materials to use for a fire drill, tinder, and kindling can mean the difference between life and death. One informant reported using the information in this story for precisely this purpose: “he and some companions were once on a fishing expedition, and had wandered too far from home to return at night. They . . . had no matches with which to start a fire. . . . Fortunately . . . they recalled the different kinds of wood to which Beaver had given fire . . . and which they understood to be . . . preferable as kindling woods. Accordingly, they took pieces of two of the kinds mentioned . . . made a small cavity in one of them, and rapidly turned the pointed end of the other therein until they were able to kindle a fire by friction” (Packard 1891:329). The information the story provides about habitat is useful for locating these woods when they are needed.

Physical Geography

This story notes that the Grande Ronde River empties into the Snake River, and that its course is straight in some places and very winding in others. The story also indicates that the banks of the upper Grande Ronde are densely forested with pine, but more thinly forested downstream. It further notes that there are no cedars along the Grande Ronde within a hundred miles of its junction with the Snake. The story also identifies a landmark–a hill near the junction of the Grande Ronde and Snake, topped by a solitary cedar tree.

This information is useful for route planning and navigation. The comment that the pine forest is “so dense that hunters can hardly get through it” suggests that land travel along this stretch of the river is difficult, making it unsuitable for hunting: dense vegetation makes it difficult to detect, track, and chase game. However, these same features make the area well-suited for eluding or hiding from pursuing enemies. The cedar is a logical choice as a landmark, because it is a long-lived species and easy to see from a distance. Upon viewing it, a traveler would know that the junction of the Grande Ronde and Snake rivers was nearby.

Grande Ronde River | Photo by Williamborg

Snake River | Photo by JD Andrews on Unsplash

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Ponderosa pine | Photo by Walter Siegmund

Cultural Geography

This story contains information about social norms: by noting that the pines guarded the secret of fire “jealously,” the story implies that it was wrong of them not to share their knowledge with others. This point is reinforced by comments on the suffering caused by the pines’ stinginess: “no matter how cold it was, nobody could get any fire to warm himself by. . . . and all the animals were in danger of freezing to death.” The story also delimits part of Nez Percé territory, in the statement that there are “no cedars within a hundred miles upstream from” the cedar landmark. This indicates that the narrator’s home range includes at least a hundred miles of the Grande Ronde upstream from the Snake.

Technology

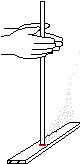

The story notes that certain types of wood ignite “when rubbed together in the ancient way.” Although it does not describe how this is done, it nevertheless tells us that fire can be made through the application of friction. Beaver’s use of a live coal to “give fire” to various tree species demonstrates an alternative, more efficient means of making fire: igniting tinder using a burning ember takes much less time, energy, and skill than making a friction fire. Beaver’s flight demonstrates that carrying live coals while traveling saves the hassle of using the friction method when making camp. The story also warns and explains why it is important to know how to make fire: “an unusually cold season came, and all the animals were in danger of freezing to death because they could get no fire.”

The Land and The People

Wallowa Mountains | Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

The Nez Percé are a nation of the Columbia River Plateau region in the Pacific Northwest. The name Nez Percé (“pierced nose”) is an exonym applied by French-Canadian fur traders and later adopted by English-speaking traders and colonists. Their autonym, Nimíipuu, means “The People” in their language, which is part of the Sahaptian family. Traditionally, Nimíipuu settlements consisted of 30-200 individuals, and were located along streams and rivers.

Prior to European contact, Nimíipuu territory encompassed approximately 27,000 square miles. It included the Clearwater and Grande Ronde rivers, as well as parts of the Salmon and Snake river drainages, extending from the Bitterroot Mountains in the east to the Wallowa and Blue Mountains in the west. This region is situated in what are now north-central Idaho, southeastern Washington, and northeastern Oregon. The terrain is characterized by wide variation in elevation and habitat, from 10,000-foot mountains to deep river canyons, from plateau prairies to densely forested valleys. Local forests consist mostly of pine, cedar, fir, and larch, with willow and cottonwood growing along streams. Summers are hot and dry, while winters are mild in the valleys but severe at higher elevations, with heavy snowfall in the mountains.

Top to bottom: camas (Camassia quamash), huckleberry (Vaccinium sp.), and wild carrot (Daucus carota) | Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

The Nimíipuu migrated seasonally throughout their territory to hunt and gather different resources. Traditional plant foods included camas bulbs, bitterroot, wild carrot, wild onion, sunflower seeds, pine nuts, and various fruits, such as huckleberry, serviceberry, gooseberry, and chokecherry. The inner bark of pine trees was eaten in times of famine, either roasted or made into a mush or soup. Important fish resources were Chinook, coho, chum, and sockeye salmon; steelhead, lake, cutthroat, and dolly varden trout; lamprey eel, sturgeon, whitefish, and several kinds of sucker fish. Ducks, geese, grouse, and sage hen were also hunted. Large game animals important in the diet were elk, deer, moose, mountain goat and sheep, and black and brown bear. Smaller game animals, such as rabbit, squirrel, badger, and marmot, were also taken. Beaver was considered a delicacy, and their teeth were used to decorate clothing. Nimíipuu hunting parties also traveled to the plains in search of bison, often with members of neighboring tribes such as the Umatilla, Cayuse, Yakima, Flathead, and Kutenai. Resource sharing was an important cultural norm.

“Sharing was mandatory, not only within a village, but among bands and even members of other tribes. Stinginess was a vice.”

—Josephy (2007:15)

The American beaver (Castor canadensis) is primarily aquatic, using its wide, flat tail and large, webbed hind feet to propel itself through the water. Kits are capable of swimming within 24 hours of birth. Beavers live in lodges, which they build on islands, along the shores of lakes, or on the banks of ponds. Alternatively, along streams and rivers that are swift or deep, they tunnel into the banks and make their nests in burrows. Their diet consists largely of bark, cambium, leaves, buds, and roots. They prefer willow, birch, maple, poplar, aspen, and alder. With their powerful jaws and incisors, they are capable of cutting through hard woods such as maple, and often fell large trees to obtain food. Like the beaver in the story, they are known to travel long distances from home in search of food. They often dig canals to connect their home with feeding areas and float food back to their lodges. This may partly explain why the story associates beavers with firewood: like beavers, humans chop down trees and haul them back to camp.

Snake River | Photo from Wikimedia Commons

The Snake River was an important travel corridor for visiting, trading, and hunting with other Indigenous nations. It provided the Nimíipuu with access to the Columbia River and its prime salmon-fishing sites at Celilo Falls and the Dalles. The Nimíipuu also attended yearly intertribal trade fairs at the confluence of the two rivers.

Fire was made using a hand-turned fire drill. The hearth board was made of willow root (Salix lasiandra Benth.) or the stem of a clematis species (Clematis ligusticifolia Nutt.). Both are found in thickets along streams, and the latter is also found on wooded hillsides and in coniferous forests. The spindle was made from the dead tips of a Pseudotsuga species, which are members of the pine family.

Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) | Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

“The legends convey moral teaching and practical information about familiar things and deal generally with notable landmarks of the Nez Perce terrain, the storms and winds of the mountains, the rattlesnakes among the basalt rocks in the canyons, the flowing streams and the salmon that come in the spring and summer, the insects, birds, animals, and trees.”

—Josephy (2007:1-2)

Boys were instructed in hunting, fishing, and riding by their grandfathers and older male relatives, while girls received instruction from their grandmothers and older female relatives. Instruction took a variety of forms. By age three or so, children began helping with various subsistence activities, such as fishing, root digging, and berry-picking. Physical training was also important: every morning before sunrise, children were awakened by their aunts and uncles for exercise and hot and cold baths, which were accompanied by lectures on proper behavior. Storytelling, too, was an important means of instruction: “Grandparents also spent many hours recounting myths, a primary means of educating the young” (Walker 1998:422).

Map

Nimíipuu territory traditionally extended from central Idaho to eastern Oregon and Washington, and encompassed the Grande Ronde, Snake, Salmon, and Clearwater River drainages.

References

Anderson, R. (2002). “Castor canadensis.” (On-lilne), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed October 2020 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Castor_canadensis/

Josephy, A. (2007). Nez Perce Country. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

Myers, P. (2000). “Castoridae.” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed October 2020 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Castoridae/.

Packard, R. L. (1891). Notes on the mythology and religion of the Nez Perces. Journal of American Folklore, 4(15), 327-330.

Spinden, H. (1908). The Nez Percé Indians. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, 2(3). Lancaster, PA: New Era Printing Company.

Walker, D., Jr. (1998). Nez Perce. In D. Walker, Jr. (Ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, Vol. 12: Plateau, pp. 420-438. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution.