“Reading the environment, or more accurately somatic listening to it, is a hunter-gatherer . . . way of gathering knowledge and understanding.”

—Low (2011:298)

“As Mbendjele hunter-gatherers . . . move about their forest they are hypersensitive to the sounds around them. All members of the party . . . react instantly to a crack, a low rumble, or an animal call by stopping mid-step, balancing on one leg if necessary. Silent and motionless, they strain to hear any follow-up sounds that will tell them whether to run for their lives, chase after their supper, or just continue onwards.”

—Lewis (2009:236)

Across forager societies, much knowledge about the local soundscape is transmitted through song. This practice capitalizes on the ability of song to communicate via two modalities: prosody and words. Thus, both vocal mimicry and lexical description can be used to encode information about the sounds animals make, the contexts in which they are made, and the inferences that can be derived from them. For example, because large animals tend to make deeper sounds than small animals, pitch can be modified to communicate information about species size and formidability. This is illustrated in a Chukchi song about a conversation between a fox and a bear: “the fox speaks in a thin treble voice; the bear answers in a deep bass voice” (Bogoras 1909:269).

Songs are often associated with a story, which furnishes additional information about the animals they reference. In some cases the song itself is a story—not unlike heroic epics such as the Odyssey and Beowulf, which are narrative poems that were traditionally sung, chanted, or recited to musical accompaniment. More commonly, however, songs are short, pithy utterances performed by animal characters. Known as animal story songs, these songs tend to reference one or more of the animal’s distinguishing traits, including vocalizations (Herzog 1935). Indeed, in some cases “the entire song is merely an imitation . . . of the animal’s cries” (Herzog 1935:9). Collectively, these songs and stories provide a catalogue of local animal sounds. For example, among the Mbendjele people of the Congo basin, “there is a common vocabulary of characteristic sounds that are regularly incorporated into accounts and stories” (Lewis 2009:238).

“The growls of animals, chirps of birds, and imitations of the sounds of nature such as rain and wind are basic elements of the melody in many Ainu songs. The tune of an epic kamuy-yukar (song of the gods) in which the hero is an animal god is typical: the sounds of animal gods, such as frogs and owls, and the imitation of sounds created by animal movements are incorporated as a refrain, while the lyrics telling the story are inserted between the refrains.”

—Tanimoto (1999:283)

Sound knowledge has numerous applications in hunting. For example, hunters commonly imitate animal vocalizations in order to lure game within shooting range. The Mbendjele people are a case in point: men attract duikers by imitating the animal’s “come frolic with me” call, and draw monkeys out of the forest canopy by imitating the sound of a fallen infant or the call of an eagle (Lewis 2009:245). As seen in the mimicry of eagle calls, hunters also lure prey by imitating an animal with which it has an inter-species relationship. For example, Kutchin men lure bears by imitating the call of a raven: “If the bear is nearby it may think a raven has discovered carrion and come straight to the sound, expecting to find a free meal” (Nelson 1973:122).

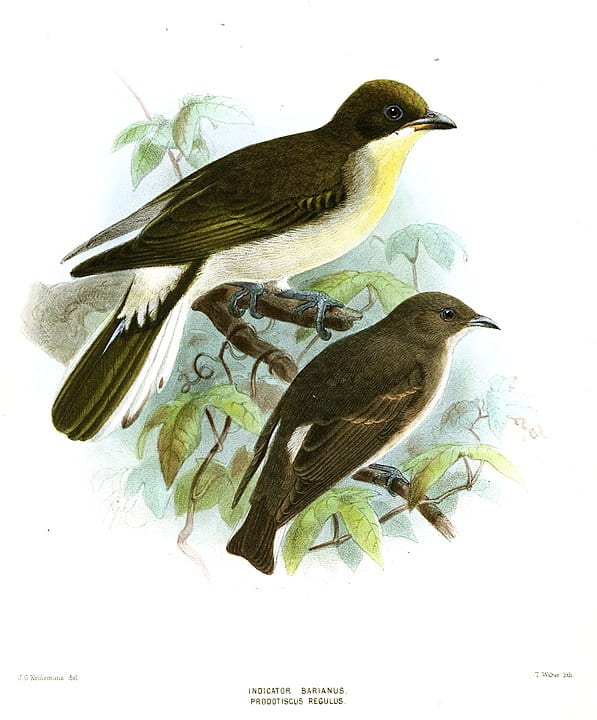

Greater honeyguide & brown-backed honeybird| John G. Keulemans

Ashy starling | Photo by Yathin S Krishnappa

Image by Matthew T. Rader

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photo by Walter Siegmund

Photo by https://www.dmitrimarkine.com/

Photo by Olga Ernst

Spider monkey | Photo by Arturo de Frias Marques

Capybara | Photo by Bob Johnson

Socratea exorrhiza | Photo by Hans Hillewaert

White-lipped peccary | Photo by I, Chrumps

“In Western Arnhem Land there used to be a lot of songs that were sung only by children and young people, or by older people who were teaching them the words and meanings. . . . Many of the words imitate bird calls and other such noises. . . . The songs help children learn and remember the habits of various creatures—where to find them, what kinds of food they like, what sort of noises they make.”

—Berndt (1979:90)

“Mbendjele listen constantly to the forest. Hearing sound signatures tells them who is there.”

—Lewis (2009:248)

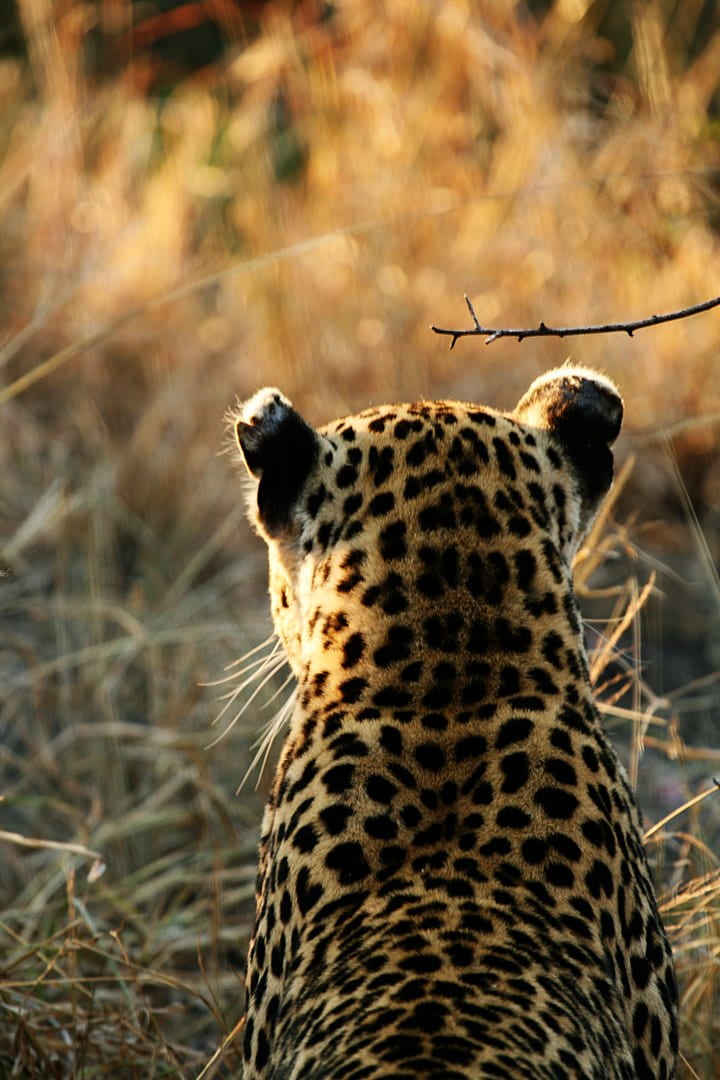

Sound knowledge is also key to interpreting animal cries. A given species may emit a range of sounds, and the meaning of a sound may vary depending on context. As Lewis observes, distinguishing “a monkey’s ‘saw a leopard’ shriek from ‘saw a pig’ yell or ‘found good food’ scream provides important information” (2009:248). Another important skill is the ability to determine whether a given noise was made by a threatening or a non-threatening agent. A description of nocturnal river noises illustrates this problem: “report of the riot at Buruhaar soon spread among the people, with the intimation that the men were coming down to wreak vengeance on their traitorous companion. At nine o’clock . . . I heard with trepidation the sound of approaching paddles . . . yet the sound did not seem to approach nearer. . . . I mentioned it to one of the men, who told me that it was a croaking frog, the paddle-frog” (Wassén 1934:628).

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

“Birds and other creatures announce changes in weather, the impending arrival of visitors, illness, and the presence of fruit, fish or snakes.”

—Sault (2010:294)

Birds are associated with a range of meteorological conditions. Among the Weenhayek, for example, the song of the kingfisher (Chloroceryle amazona) is believed to forecast sunshine (Alvarsson 2012:106). The Klamath people of Oregon and California associate the male kals with fog: “This is my song, the kalsh-bird’s, who made the fog” (Gatschet 1890:166). Gatschet explains that the “kals flies around in cold nights followed often by foggy mornings, hence the belief that it makes the fog” (1890:172). The tsiutsíwäsh-bird, on the other hand, is believed to herald the arrival of snow: “The snow made by me, the tsiutsíwäsh-bird, is ready to arrive” (Gatschet 1890:170).

Listening to stories and songs that use vocal mimicry enables the audience to learn (or refresh their memory of) what sounds to attend to and what those sounds mean. The Mbendjele are a case in point: “Hearing these sound signatures while listening to people’s accounts of their experiences both reminds and educates listeners. Younger listeners’ attention is drawn to key warning sounds, and all are reminded of the actions behind the sounds, and what to do or not to do in response” (Lewis 2009:238). Performers benefit too: in the course of mastering these songs and stories, they learn how to produce these ambient sounds themselves. Every performance provides an opportunity to rehearse these skills. As Lewis explains, the Mbendjele “pay careful attention to the sounds of the forest and take pride in mimicking them precisely when recounting their day or chatting. When describing an encounter with a forest animal great attention is paid to . . . meticulous mimicry of the sounds of the encounter, from the thrashing of trees, to the calls or hoots of the animal” (Lewis 2009:238).

Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

“men re-enact great hunting moments by making all the key sounds as exactly as possible, but also by performing the classic postures and moves of themselves and the animal as the tale unfolds. . . . It is in these moments that the key tactics for approaching different prey animals are discussed and debated, subtle techniques for finding honey and other prized foods are shared, and the youth learn about the key postures and sounds animals and hunters make to guide them during forest encounters. It is in these ways that young men begin their apprenticeship in advanced hunting techniques.”

—Lewis (2009:239)

Berndt, C. (1979). Land of the Rainbow Snake: Aboriginal Children’s Stories and Songs from Western Arnhem Land. Sydney: Collins.

Blurton Jones, N. & Konner, M. (1976). !Kung Knowledge of Animal Behavior. In R. B. Lee & I. DeVore (Eds.), Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers, 325-348. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bogoras, W. (1909). The Chukchee. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

Gatschet, A. (1890). The Klamath Indians of Southwestern Oregon. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Herzog, G. (1935). Special Song Types in North American Indian Music. Berlin: Gesellschaft Für Vergleichende Musikwissenschaft.

Hill, K. & Hurtado, A. M. (1996). Ache Life History: The Ecology and Demography of a Foraging People. London: Routledge.

Lewis, J. (2009). As well as words: Congo Pygmy hunting, mimicry, and play. In R. Botha & C. Knight (Eds.), The Cradle of Language, 236-256. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Low, Cs. (2011). Birds and Khoesān: Linking spirits and healing with day-to-day life. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 81, 295-313.

Massola, A. (1968). Bunjil’s Cave: Myths, Legends and Superstitions of the Aborigines of South-East Australia. Melbourne: Lansdowne Press.

Nelson, R. (1973). Hunters of the Northern Forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nelson, R. (1983). Make Prayers to the Raven: A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peterson, D., Baalow, R., & Cox, J. (2013). Hadzabe: By The Light of a Million Fires. Dar-es-Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota.

Reyes-García, V. & Fernández-Llamazares, A.. (2019). Sing to learn: The role of songs in the transmission of Indigenous knowledge among the Tsimane’ of Bolivian Amazonia. Journal of Ethnobiology, 39, 460-77.

Roth, W. (1915). An Inquiry into the Animism and Folklore of the Guiana Indians. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Sault, N. (2010). Bird messengers for all seasons: Landscapes of knowledge among the Bribri of Costa Rica. In S. Tidemann & A. Gosier (Eds.), Ethno-Ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society, 291-300. London: Earthscan.

Tanimoto, K. (1999). To live is to sing. In W. Fitzhugh & C. Dubreuil (Eds.), Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, 282-285. Washington: Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

Wassén, H. (1934). The frog in Indian mythology and imaginative world. Anthropos, 29, 613-658.

Wilbert, J. (1996). Mindful of Famine: Religious Climatology of the Warao Indians. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Yost, J. A. & Kelley, P. M. (1983). Shotguns, blowguns, and spears: the analysis of technological efficiency. In W. Vickers & R. Hames (Eds.), Adaptive Responses of Native Amazonians, 189-224. New York: Academic Press.