“The Fight Against the Tschouds”

Culture: Saami | Narrator: Unidentified | Source: Bernatzik & Ogilvie (1938:125)

Entry by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Story

Nota bene: This story is a retelling by the collectors, and thus not told in the exact words of the informant; the ethnonym used in the story (i.e., Lapps) is rejected by the Saami people.

Many legends tell of the fights against a wild robber people, the Tschouds. The Tschouds used to rob the Lapps in order to force them to show them the way. In late autumn, when the nights had turned darker, a clever young Lapp hatched a plan for sending them to destruction. The Lapps were at the time on their way back from the mountains and were camping on the Vuorektj akko, where they had lit their fires. The Lapp purposely let himself be captured by the Tschouds and led them from the west over the Räkker, which falls steeply towards the Vuorek. When the Tschouds saw the fire of the Lapp encampment they were delighted to have at last reached the enemy, hurried forward and in the darkness failed to see the valley that lay between them and the Lapps. Their guide went ahead, carrying a kolte over his arm. Talking carelessly the while, he struck a light with his tinder and set fire to the kolte. When he came to the edge of the precipice he threw the burning kolte over, jumped aside and vanished in the darkness. The Tschouds followed the fire, which they supposed the guide to be still carrying, and one after another fell over the precipice and lay smashed to pieces below. As the last man was about to go over the Lapp held him back and saved him, to tell the story of the disaster. The Lapps on the other side of the valley heard the cries and knew that the plan had succeeded. They sent the survivor to the other Tschouds and told him to say, “If you want to see the disaster on the Räkker, come here!” The Tschouds were afraid and departed.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Physical Geography

This story contains information about local topography, noting that the Räkker falls steeply towards the Vuorek, and that there is a precipitous valley between the Räkker and the Vuorektj akko. The story also identifies a travel route and indicates the location of various places relative to each other. A person listening to this story would learn that there is a route over the Räkker, that this route leads to the Vuorek, that the Vuorek lies to the east of the Räkker, and that there is a good campsite along the Vuorektj akko. The story also indicates that this route is navigable in late autumn.

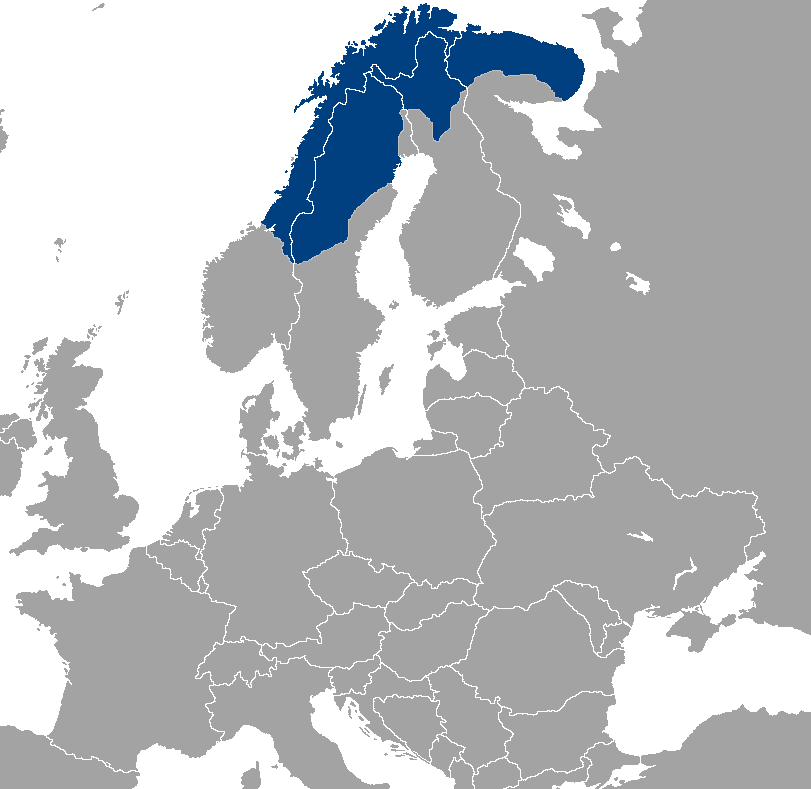

Saami territory | Image from Wikimedia

Cultural Geography

This story provides demographic information, indicating that the Tschouds are hostile toward the Saami people, and live in (or approach from) an area west of Saami territory. The observation that the Tschouds were “delighted to have at last reached the enemy” suggests that they lived at a considerable distance from the Saami.

Technology

This story describes a defensive strategy that may be used when a group finds itself threatened by a more powerful enemy force. The strategy is to literally mis-lead the enemy by guiding them away from their target and/or into a situation that thwarts their attack. In this case, the young Saami man pretends to be guiding the enemy to his people’s camp while actually leading them off a cliff. The story also describes the specific tactics used to achieve this. First, the young man lets the Tschouds capture him, knowing that they will try to coerce him into leading them to the Saami camp. This enables him to choose the route, which in turn enables him to maneuver the Tschouds onto the edge of a precipice. To do this, he exploits the darkness, which obscures the trail, the cliff, and the chasm below. It also serves as a pretext for lighting the kolte, and sustains the illusion that the man is using the light to guide the Tschouds along the trail even after he has thrown it into the chasm.

Hikers in Abisko National Park | Photo by Josefin Brosche Hagsgård

Saami camp, 1818 | Painting by Aleksander Lauréus

Fire-making kit | Photo by Dirk van der Made

The story also identifies the equipment needed to implement this tactic: a fire-making kit. In so doing, the story underscores the importance of being prepared for emergencies by always carrying basic survival tools. The story also shows that terrain (e.g., cliffs) and ambient conditions (e.g., darkness) can serve as “equipment”—as resources that can be deployed to strategic advantage in warfare. This highlights the importance of paying attention to your surroundings: it might save your life one day.

Further precautionary information is seen in the observation that the Tschouds “hurried forward” when they saw the Saami campfires. This rash act cost them their lives, demonstrating that it is best to proceed slowly and warily when traveling over unfamiliar, hazardous terrain at night. Another lesson is seen in the Tschouds’ underestimation of the Saami youth’s capabilities and position: in their haste to rob the Saami camp, the Tschouds fail to consider that their Saami guide has home field advantage. This points to another strategy: your enemy’s greed and hubris may cause them to lower their guard, which you can then use against them.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Yet another strategy is seen when the life of one of the would-be raiders is spared, on the condition that he tell the rest of the Tschouds what happened to their war party. This strategy uses intimidation to reduce the likelihood of further attack. The message the man is commanded to deliver is an implied threat: “If you want to see the disaster on the Räkker, come here!” The subtext of this message is that, should the Tschouds send another war party, the Saami will destroy it as well. The eyewitness testimony of the messenger serves as evidence that the Saami are perfectly capable of executing this threat.

The story also provides information about the effectiveness of these tactics, noting that when the Saami people heard the cries of the Tschouds falling off the cliff, they “knew that the plan had succeeded.” Their intimidation tactic was also successful: when the Tschouds learned of the fate of their war party, they “were afraid and departed.”

Photo by Rotehodet

The Land and The People

Saami Family, 1936 | Photo by Kortcentralen Helsingfors

The Saami are one of the few ethnographically documented hunting-and-gathering peoples on the European continent. The first known written reference to the Saami occurs in Tacitus’ Germania in AD 98. In the historical record, they are commonly referred to as Lapps or Laplanders, but these exonyms are rejected by the Saami themselves. There are nine extant Saami languages, which are closely related but mutually unintelligible. These languages are part of the western division of the Finno-Ugric branch of the Uralic family. Close linguistic relatives include Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian.

The Saami traditional homeland, Sápmi, spans the northernmost reaches of four modern nation states: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. This territory of 150,000 square miles is bordered by the Norwegian Sea to the west, the Barents Sea to the north, and the White Sea to the East. Encompassing arctic and subarctic regions, the world of the Saami consists primarily of tundra, taiga, and coastal zones. Summers are short and mild, with temperatures rarely exceeding 25 degrees Celsius. Winters are long and cold, with snow cover from October to May, and temperatures dropping as low as -40 degrees Celsius.

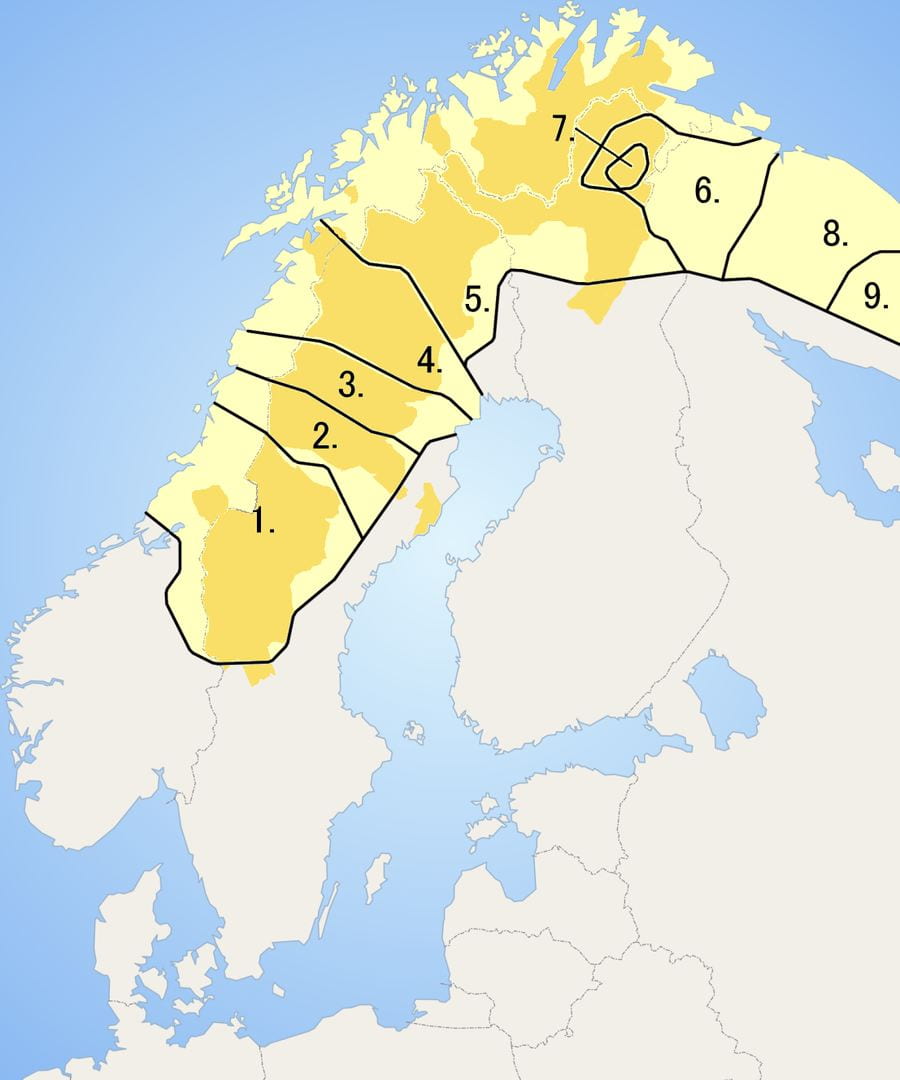

Distribution of Saami languages | Image by Misha bb

Lapland Province, Sweden | Photo by DiHib

Sápmi is bisected from north to south by a long, rugged mountain chain. The upper elevations are dominated by treeless heaths, while the valleys are heavily forested with birch, Scots pine, and Norway spruce. The region abounds with lakes, rivers, and marshes, where deciduous trees such as alder and willow are concentrated.

“The Fennoscandian mountain ridge stretches north-south and includes steep rocky areas intersected by deep valleys. . . . On the Norwegian side, mountain peaks reach almost 2000m above sea level, and hillsides fall steeply into the fjords. The peaks are somewhat lower on the Swedish side, generally reaching 500 to 1000m above sea level. Glaciers occur at high altitudes, exceeding approximately 1500m above sea level on both sides of the border.”

—Bergman et al. (2007:398)

Drying fish, Varanger Peninsula | By kalev kevad

The Saami can be divided into three major subgroups that differ in subsistence patterns: Mountain Saami, Forest Saami, and Coastal (or Fisher) Saami. All were nomadic to a certain extent. The Forest Saami, for example, moved from lake to lake to take advantage of successive spawning runs. The Coastal Saami spent the summer fishing, wildfowling, and egg collecting along fjords and coastal islands, and moved inland for hunting and ice fishing in the winter.

Traditionally, all of these groups made their living by a combination of hunting, trapping, fishing, and gathering. Important plant foods included cloudberries, lingonberries, and the inner bark of Scots pine. The sea provided seal, whale, and walrus, while the many lakes and rivers provided whitefish, Arctic char, salmon trout, trout, grayling, and northern pike. The latter was preserved by drying and stored for later use. A wide range of land mammals were trapped and hunted for their meat and fur: red squirrel, ermine, European pine marten, hare, beaver, red fox, wolverine, bear, moose, and reindeer. Economically, the reindeer was the most important land mammal, not only for food, but also for boots, clothing, and implements. A few tame reindeer were kept for use as riding and draft animals, and as hunting decoys. Hunting methods varied, depending on the season.

Photo by Alexandre Buisse (Nattfodd)

Saami hunting on skis, 1555 | Image by Olaus Magnus

Photo by Phil Myers

“In Autumn, at their rutting Time, they catch them by exposing to their view a tame Female Raindeer; and whilst they are approaching, the Hunts-man, who hides himself behind the tame Doe, shoots them with his Fire-Arms. . . . In the Spring they overtake them by the help of their Scates tyed to their Feet, whilst they are entangled in the deep Snows. . . . They have also a way of forcing them into Snares with Dogs. . . . Last of all they catch them by the help of Nets or Hurdles, set up on both Sides for a considerable length, betwixt which they are forced or chased to the end of the Enclosure, into a Pit Dug there for that Purpose.”

—Scheffer (1704:237-238)

Eventually, some Saami populations adopted reindeer pastoralism. Scholars disagree over when this transition occurred: some situate it in the first millennium AD, others in the sixteenth century, and still others in the second half of the eighteenth century. Archaeological and ethno-historical evidence indicate that the transition to reindeer herding was gradual and localized, being adopted by different groups at different times. According to Odner (1992:40), for example, the Kola, Skolt, and Enari Saami made their living by hunting and fishing until the nineteenth century, and Josefsson et al. (2010:142) report that “hunting, fishing, and gathering of edible plants remained key parts of Sami subsistence until the beginning of the twentieth century.”

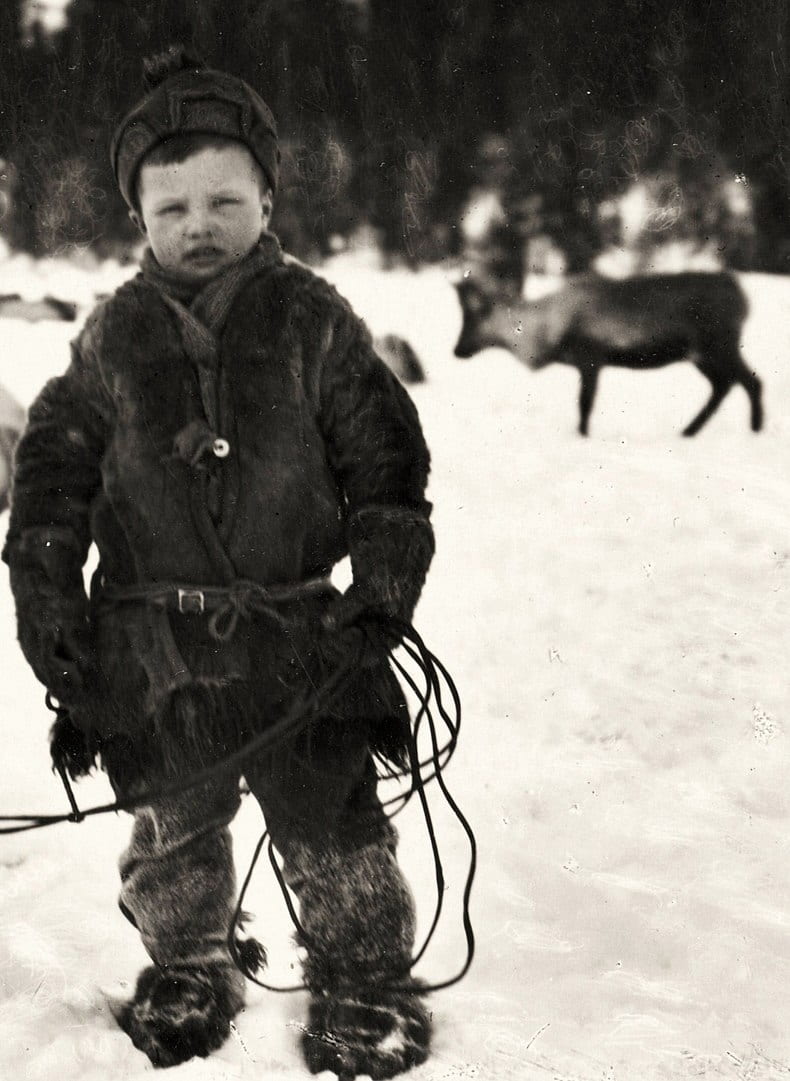

Saami child, 1923 | Photo from Wikimedia

Reindeer-skin coat | Photo by Wilhelm Abraham Eurenius

The accounts of early European traders and explorers indicate that most Saami continued to live primarily by hunting, gathering, and fishing until approximately 1500 AD, when increasing economic pressure from neighboring polities necessitated greater wild reindeer exploitation. Early in the Viking era, Norse merchants initiated trade with the Saami. This led to taxation by several Nordic kingdoms, who regarded the Saami as their subjects. By the sixteenth century, these taxes–which were paid in furs, dried fish, and reindeer-skin clothes–had become excessive, with the Saami of the far north paying tribute to three states simultaneously. By the seventeenth century, the heavy tax burden had greatly reduced the wild reindeer population, and the Saami had to implement new subsistence strategies.

The Mountain Saami became pastoralists, subsisting largely on reindeer meat and milk products. The Forest Saami combined reindeer herding with wild reindeer hunting and fishing, and the Coastal Saami survived by exploiting marine resources more intensively. Thus, only a small subset of the Saami population adopted pastoralism; for most families, wild resources remained an important part of the diet into the early twentieth century.

Photo by NOAA

Saami man | Painting by François-Auguste Biard

“Travelling in the mountains was always difficult and dangerous. Streams had to be crossed and steep slopes climbed, while bogs and rocky fields hindered the passage. During the spring, snow melting generated powerful rapids and during the winter snowstorms and avalanches endangered travelers. During the winter, lakes and watercourses offered convenient routes, but snowstorms and holes in the ice were frequent obstacles. . . . It took skill and experience to travel safely in the high mountain area.”

—Bergman et al. (2007:399)

Many Saami legends recount conflicts with a fierce Finno-Ugrian tribe called the Tschouds (also spelled Čudi, Chudi, Tsjudi, and Sudi). Their exact identity is unknown: the name may refer to Karelian tribes or to the Finnish tribe known as the Ves. Others posit that it is a catch-all term for parties of marauding Karelians, Russians, Swedes and Norwegians, by whom the Saami were beleaguered from the thirteenth to the fifteenth century. The tales recount how the Saami used their intimate knowledge of their territory to outwit these invaders, who underestimated the hazards of traversing this rugged land.

Galdhøpiggen Mountain | Photo by Håvard Berland

Abisko National Park | Photo by Witext

Map

The Saami traditional homeland, Sápmi, spans the northernmost regions of four modern nation states: Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia.

References

Anderson, M. & Beach, H. (1996). Culture summary: Saami. Human Relations Area Files (HRAF).

Bergman, I., Östlund, L., Zackrisson, O., & Liedgren, L. (2007). Stones in the snow: a Norse fur traders’ road into Sami country. Antiquity, 81:397-408.

Bernatzik, H. & Ogilvie, V. (1938). Overland with the Nomad Lapps. New York: Robert M. McBride & Co.

Josefsson, T., Bergman, I., & Östlund, L. (2010). Quantifying Sami settlement and movement patterns in northern Sweden 1700-1900. Arctic, 63(2):141-154.

Meriot, C. (1984). The Saami peoples from the time of the voyage of Ottar to Thomas von Westen. Arctic, 37(4):373-384.

Norstedt, G., Axelsson, A., Östlund, L., & Giguère, N. (2014). Exploring pre-colonial resource control of individual Sami households. Arctic, 67(2):223-237.

Odner, Knut. (1992). The Varanger Saami: Habitation and Economy AD 1200-1900. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Scheffer, J. (1704). The History of Lapland: Containing a Geogrpahical Description, and a Natural History of that Country; with an Account of the Inhabitants, Their Original, Religion, Customs, Habits, Marriages, Conjurations, Employments, etc. Printed for Tho. Newborough, at the Golden-Ball in St. Paul’s Church-Yard and R. Parker under the Royal-Exchange.