“Raven and Owl”

Culture: Oráwêtlat (Chukchi) | Narrator: Raa’nau | Source: Bogoras (1910:158)

Entry by Averie Skeels and Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Story

Raven and Owl fought for a hare. Owl caught Raven by the throat with one of his claws. Raven cries, “Don’t you dare to eat my hare! I wish to eat it. I am the hunter,” because he is so fond of big talking. Owl was silent, but he clenched Raven’s throat so tightly that Raven gave way. Owl took the hare and wanted to eat it. Then Fox assaulted him. The Fox cried, “I am the great hunter! I kill everything, even the mouse and the spermophylus.” Owl was silent, and wanted to eat the hare. They fought. Fox bit Owl’s back. He was the stronger of the two. Owl desisted and flew up. From mere shame he quite refused to perch again on that place. The silent one also was not a victor. The end.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Zoology

This story indicates that ravens, owls, and foxes all eat hares and that, by implication, they are carnivorous. The fox’s boast tells us that its diet also includes mice and ground squirrels (“spermophylus”). The trio’s dispute over the hare suggests that these species are food competitors in real life. Specifically, it indicates that owls attack and steal food from ravens, and that foxes attack and steal food from owls. The story does not mention how the raven acquired the hare, suggesting that it has been scavenged; the theft of the carcass, first by the owl and then by the fox, implies that these species scavenge as well.

Photo by Jongsun Lee

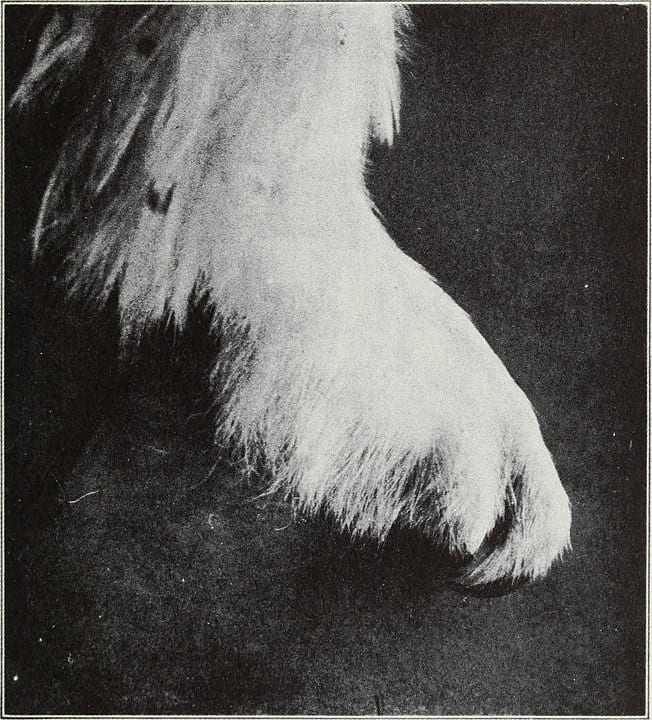

Snowy owl talon | Photo from Wikimedia

The story also provides information about animal traits. The observation that the fox was “the stronger of the two” implies that foxes are more powerful than owls. Similarly, the fact that the raven gives way to the owl implies that owls are stronger than ravens. The reference to the owl’s claws provides information about this animal’s morphology, and the repeated references to owl’s silence indicate that it is a quiet and stealthy animal. In contrast, the comment that raven is fond of “big talking” suggests that this animal is noisy.

The story also provides information about animal behavior. Because “big talking” connotes bragging, the story implies that the raven’s claim to be a hunter is exaggerated or false. Significantly, the fox’s claim that he is a great hunter is not characterized as “big talking,” suggesting that this observation is accurate. The story also provides information about the animals’ mode of attack: the owl kills by grabbing the throat, and the fox by biting the back. The fact that the owl escapes by flying away indicates that the fighting among the three species takes place on the ground, which in turn suggests that ravens and owls are partly terrestrial. The reference to the owl perching indicates that this species is also partly arboreal.

Photo from Wikimedia

The story identifies several inter-species relationships. It indicates that the habitats of ravens, owls, foxes, hares, mice, and ground squirrels overlap or intersect with one another. It also identifies a number of predator-prey relationships: mice and ground squirrels are hunted by foxes, and hares are hunted by both foxes and owls.

Technology

This story alludes to several hunting and trapping strategies. This is seen in the information that ravens, owls, and foxes engage in scavenging and kleptoparasitism (i.e., stealing each other’s food), and that they share habitat with species targeted by humans (e.g., hares and ground squirrels). This suggests that humans can follow the sounds, tracks, and/or flight of ravens, owls, and foxes to locate and steal carcasses. The observations that owls are silent and ravens are noisy indicate that the latter are easier to detect and follow. The information that these animals compete over carcasses suggests that the noise of their fighting is something to listen for when searching for game.

Photo by Karl Friedrich Herhold

The claim that foxes are great hunters suggests that the chances of finding game by following this animal are good. It also implies that fox tracks can be followed to locate the tracks, territories, and burrows of prey species, which is useful for deciding where to place snares. Also, knowing what foxes eat is useful for deciding where to place fox traps and what to bait them with.

The Land and The People

The Chukchi people live in northeastern Siberia and consist of two main groups: the reindeer Chukchi and the coastal Chukchi. Both speak the Chukchi language, and refer to themselves collectively as Oráwêtlat (“men”) or Lîeoráwêtlat (“genuine men”). The name Chukchi is an exonymn applied to them by the Russians; it is derived from the Chukchi word cháwtcy, which means “rich in reindeer.” The reindeer Chukchi adopted this name to distinguish themselves from their coastal counterparts, who call themselves Añkalît, meaning “sea people.”

As implied by their names, the traditional economies of these two groups differed considerably. The maritime Chukchi subsisted by hunting sea animals and fishing, while the reindeer Chukchi made their living by hunting, trapping, and reindeer herding. Because large herds require frequent change of pasture, the reindeer Chukchi were highly nomadic, spending most of the year moving from camp to camp on the tundra over a range of 100 to 150 miles. In contrast, the maritime Chukchi lived a more settled existence. These groups were further divided into bands, each of which occupied a different territory. In more recent times, the villages of the coastal Chukchi consisted of several related and unrelated families. However, in the early twentieth century, there were still villages comprised entirely of relatives, suggesting that settlements were traditionally kin-based.

The reindeer Chukchi lived in camps of four or five families who held their reindeer in common. The neighbors of the reindeer and coastal Chukchi peoples included the Yupik along the Bering Sea coast, the Koryak to the south, and the Yakuts and Yukaghir west of the Kolyma River.

Photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

The reindeer and coastal Chukchi bartered with each other to acquire resources that were unavailable in their own territories. The reindeer Chukchi offered reindeer skins and garments in exchange for sea mammal skins and oil. Fox pelts, too, were highly prized. The meat of the fox, however, was regarded as poor people’s food. In contrast, ground squirrels were valued for both their fur and their meat, the latter of which contains a high degree of fat in late summer as hibernation approaches. The Chukchi also hunted seabirds, partridge, and eider ducks. Small mammals–such as ground squirrels, hares, and marmots–were caught with snares. Mice were important not as food, but for the roots they stored in their burrows, which were collected by women.

The reports of early Russian explorers indicate that the traditional homeland of the Chukchi stretched from the Chukchi Sea to the north, the Bering Strait to the east, the Bering Sea to the south, and the Kolyma River to the west. The northern reaches, which include the Chukchi Peninsula and the north slope of the Anadyr Range, lie in the tundra zone. The climate is characterized by dampness, fog, and extremely low temperatures. Rivers are frozen from mid-October to early June, and ice is present in the Chukchi Sea throughout the summer. The region west of the Anadyr Highlands consists of tundra and mountain taiga, with meadows and bogs throughout the valleys. To the east lie the Anadyr Lowlands, a region of flat tundra dotted with lakes and bogs. The flora of the Anadyr Basin consists largely of dwarf cedar and alder thickets. Poplar and birch grow along the river valleys; larch is found along the Mayn River and upper reaches of the Anadyr.

Common ravens, snowy owls, arctic foxes, arctic hares, and arctic ground squirrels are found throughout the tundra and taiga regions of eastern Siberia, both on the coast and in the interior. Of the five species, only the ground squirrel hibernates. Ravens, owls, and foxes all kill or scavenge small game, and compete with one another for food. On average, snowy owls are somewhat larger than common ravens, with the former weighing 1450 to 1600 grams and the latter weighing 689 to 1625 grams. At an average of 2900 to 3200 grams, the fox is by far the heaviest. Thus, in a food dispute, an owl is likely to outweigh and out-compete a raven, and a fox is likely to beat them both, as seen in the story.

Although they are known to hunt, ravens are primarily scavengers: in addition to carrion and the insects that feed on it, they eat arthropods, amphibians, small mammals, birds, and reptiles. The snowy owl is a silent hunter, relying on the element of surprise to grab its victim by the neck. It subsists mainly on lemmings and mice, but takes hares, fish, and seabirds opportunistically. It is also known to scavenge reindeer, walrus, and whale carcasses, and will follow polar bears in order to feed on their kills. The snowy owl also engages in kleptoparasitism, stealing game from other birds of prey and from traps set by humans. As indicated in the story, the arctic fox hunts a wide range of prey: it is capable of catching invertebrates, fish, birds (including owls), small mammals (e.g., hares, ground squirrels, mice, lemmings), and even baby seals. Like the common raven and snowy owl, however, it is an opportunistic feeder, known to avail itself of carrion (including polar bear kills), as well as eggs, berries, and feces.

Arctic fox, summer pelage | Photo by Hillebrand Steve

Arctic ground squirrel | Photo by Bureau of Land Management

Ravens are equally comfortable in the air, on the ground, or on a perch. As shown in the story, they are noisy animals, known for their frequent and loud vocalizations. Although snowy owls are capable flyers and swimmers, they spend most of their time on the ground. They prefer flat surfaces, and tend to perch only when scanning the horizon for prey.

Photo by Peter K Burian

Arctic hares and ground squirrels are an important part of the Siberian food chain: both are hunted by arctic foxes, snowy owls, and humans, and ground squirrels are taken by ravens as well. Many predators in the region shift to ground squirrels when the hare population periodically crashes.

Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Map

The traditional homeland of the Chukchi is the Chukotka Peninsula, bordered by the Chukchi Sea to the north, the Bering Strait to the east, and the Bering Sea to the south.

References

Antropova, V. V. & Kuznetsova, V. G. (1964). The Chukchi. In M. G. Levin & L. P. Potapov (Eds.), The Peoples of Siberia, 799-835. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Atkinson, R. (2002). “Nyctea scandiaca” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 21, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Nyctea_scandiaca/

Berg, R. (1999). “Corvus corax” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 21, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Corvus_corax/

Betzler, B. (2015). “Lepus arcticus” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 21, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Lepus_arcticus/

Bogoras, W. (1901). The Chukchi of Northeastern Asia. American Anthropologist, 3(1), 80-108.

Bogoras, W. (1909). The Chukchee. Leiden: F. J. Brill.

Bogoras, W. (1910). Chukchee Mythology. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Brooks, W. S. (1915). Notes on Birds from East Siberia. Cambridge, MA: U.S.A. Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Cholewiak, D. 2003. “Strigiformes” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 24, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Strigiformes/

Embar, K., Raveh, A., Burns, D., & Kotler, B. (2014). To dare or not to dare? Risk management by owls in a predator–prey foraging game. Oecologia, 175(3), 825-834.

McBryde, B. (2004). “Corvus caurinus” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 24, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Corvus_caurinus/

Middlebrook, C. (2007). “Vulpes lagopus” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 21, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Vulpes_lagopus/

Oien, E. (2011). “Bubo blakistoni” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 24, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Bubo_blakistoni/

Slaght, J. & Surmach, S. (2008). Biology and conservation of Blakiston’s fish-owls (Ketupa Blakistoni) in Russia: A review of the primary literature and an assessment of the secondary literature. Journal of Raptor Research, 42(1), 29-37.

Torre, N. (2013). “Spermophilus parryii” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed July 21, 2021 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Spermophilus_parryii/