Kamilaroi & Euahlayi Astronomy

Entry by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

The Kamilaroi and Euahlayi are Aboriginal peoples of southeast Australia who speak related languages. Euahlayi territory lies in the northwest of New South Wales, while Kamilaroi territory stretches from New South Wales to southern Queensland. Both groups utilized the Barwon River wetlands area.

Barwon River | Photo by Cgoodwin

Milky Way | Photo by Steve Jurvetson

One of the most important figures in Kamilaroi and Euahlayi astronomy is the Emu in the Sky, or Sky Emu. This constellation is unusual in that it consists of nebulae—gas and dust clouds–rather than stars. The head of the emu is formed by the Coalsack Nebula, a dark patch in the Milky Way located next to the Southern Cross (also known as Crux). Other dark nebulae in the Milky Way form the emu’s body.

Sky Emu | Image by en:User:Rayd8

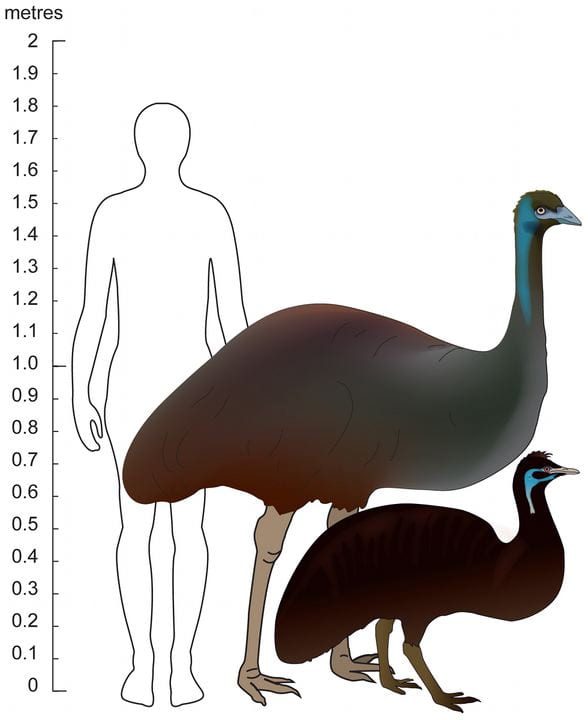

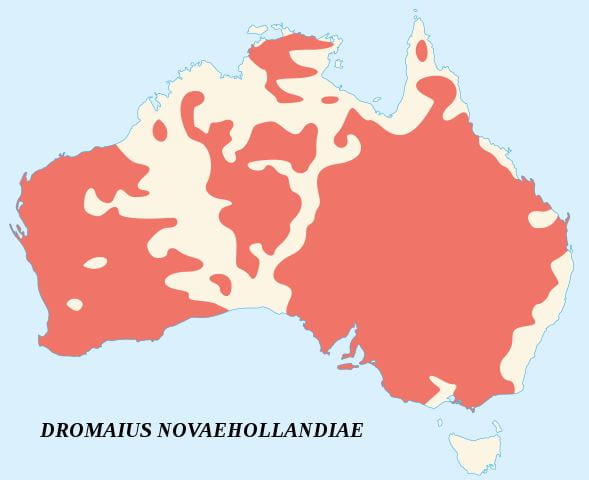

Emus (Dromaius novaehollandiae) occur widely across the Australian mainland and were regularly hunted by many Aboriginal peoples, including the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi. A relative of the ostrich, this bird was a prized food resource due to its large size: adults average five feet in height and can weigh up to 130 pounds. At over a pound each, their eggs were an important source of nutrition as well. A smaller island-dwelling emu species became extinct after European colonization of Australia.

Human, emu, & island emu | TH Heupink, L Huynen & DM Lambert

Photo by Sklmsta

Emus are not easily captured. Though flightless, they are well-adapted for running, and can sustain speeds of over 30 miles per hour (Tonkinson 1978). Their powerful legs also serve as formidable weapons, which they use for self-defense.

“I have seen a large kangaroo-dog knocked over two or three times by a stroke from the leg of an emu.”

–Smyth (1878:192)

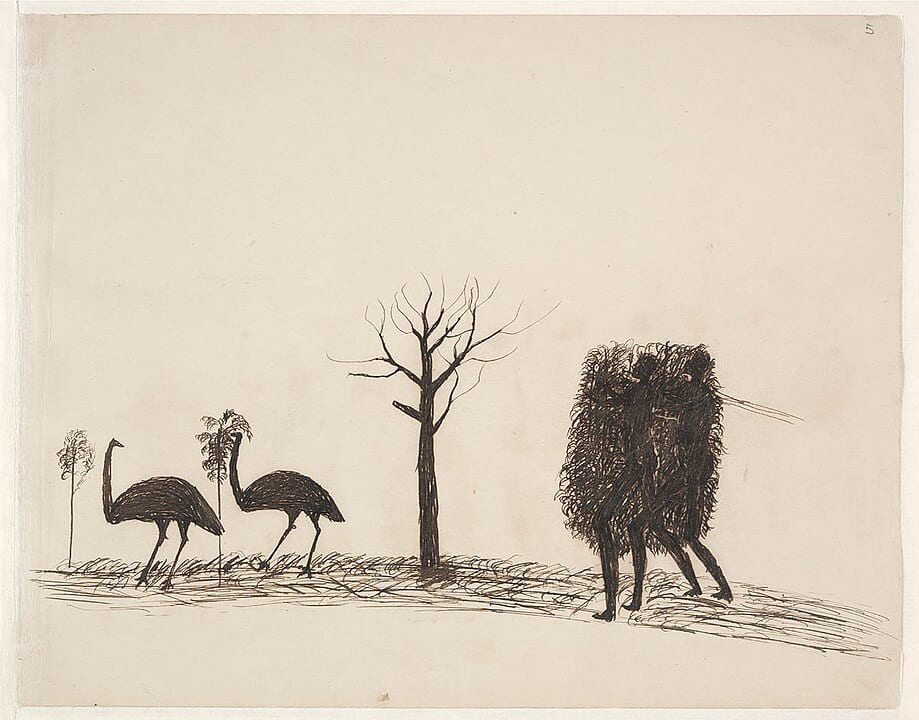

Emu presence in a given area depends heavily on favorable water conditions. Accordingly, emus were often hunted from blinds at water holes (Gould 1969) or rivers. For example, the Ngarrindjeri would spear emus as they made their way down a cliff to drink from the Murray River (Clarke 2018).

Murray River | Photo by Scott Davis

Image by Tommy McRae

“In some parts the leaves of the pituri plant (Duboisia Hopwoodii) are used to stupefy the emu. The plan adopted is to make a decoction in some small waterhole at which the animal is accustomed to drink. . . . Sometimes a bush shelter is made, so as to look as natural as possible, close by a waterhole, and from behind this animals are speared as they come down to drink.”

–Spencer & Gillen (1899:20)

“Small and shallow catchments are sometimes covered with sticks, stones, grass, or boughs, possibly to cut down evaporation, but when several such holes occur together, the blocking of all but one is part of the Mardudjara’s emu hunting strategy.”

—Tonkinson (1978:23)

Photo by J. Folmer

Emu distribution | Image by Sémhur

The Emu in the Sky encodes information that is useful for hunting emus and their eggs. Over the course of the year, the Milky Way changes position in the night sky. This causes changes in the orientation and visibility of the Sky Emu. These changes are correlated with changes in emu and water availability from season to season. The Emu begins to appear in March, when only its head and neck are visible. In April and May its entire body can be seen. At this time, which coincides with the breeding season, the people say that the Emu has legs and appears to be running. This is a reference to a distinctive feature of emu mating behavior, in which the females chase the males. (In emus, females are the sex that competes for mates and is more aggressive during breeding.) Courtship behavior is an indication that emu eggs will soon be available.

In June and July, the Sky Emu’s legs disappear, and the bird is now perceived as a male sitting on its nest, hatching the new chicks. This image encodes further information about emu reproduction: the task of incubation is performed by males. At this time, the eggs are still edible and can be taken from the nest.

Photo by Shuhari

Photo by Vcarceler

In August and September, the Emu’s neck becomes indistinct, and its body is viewed as an emu egg. This change correlates with the hatching of the chicks, and signals that eggs are no longer available. In November, the Emu appears low in the sky, and its neck and head are difficult to see. As a result, the Emu appears to be sitting on the horizon, which is interpreted as a waterhole. This image encodes the information that waterholes are now likely to be full, which is normally the case at this time of year.

As the Australian summer begins in late December, the Sky Emu gradually sinks below the horizon. At this point the Emu is said to have left the waterholes, signifying that they are now dry. The Emu won’t be visible again until March, when the cycle repeats.

Crux and the Coal Sack Nebula | Photo by Naskies

“an Aboriginal [person] . . . knows the habits and the anatomy and the haunts of every animal in the bush. He knows all the birds, their habits, and even their love, or mating, notes. He knows the approach of the different seasons of the year from various signs, as well as from the positions of the stars in the heavens. . . . All the stars and constellations in the heavens, the Milky Way, the Southern Cross, Orion’s Belt, the Magellan Cloud, etc., have a meaning. There are legends associated with them all.”

–Unaipon (2001:6-7)

References

Clarke, P. (2018). The Ngarringdjeri nomenclature of birds in the Lower Murray River region, South Australia. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. https://doi.org/10.1080/03721426.2018.1534530

Fuller, R., M. G. Anderson, R. P. Norris, & M. Trudgett. (2014). The Emu sky knowledge of the Kamilaroi and Euahlayi peoples. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 17(2), 1-13.

Gould, R. (1969). Yiwara: Foragers of the Australian Desert. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Smyth, R. Brough. (1878). The Aborigines of Victoria: With Notes Relating to the Habits of the Natives of Other Parts of Australia and Tasmania. Melbourne: John Ferres.

Spencer, B. & F. Gillen. (1899). The Native Tribes of Central Australia. London: Macmillan.

Tonkinson, R. (1978). The Mardudjara Aborigines: Living the Dream in Australia’s Desert. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Unaipon, D. (2001). Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. S. Muecke and A. Shoemaker (Eds.). Melbourne University Press.