Story Worlds

Navigating Narrative Landscapes

Photo by Lawrence Sugiyama

Travel Tips

Helpful concepts to take along on your journey

Performed Narrative

The stories on this site were traditionally performed orally, and utilize stylistic devices not commonly seen in written narrative, such as repetition, song, direct discourse, mimicry, and formulaic phrases (e.g., “That is why . . .”). Narrators use these devices to engage audience attention and emphasize certain moments in the story. This encourages the audience to concentrate and commit particulars to memory. Take note of these devices as you travel through hunter-gatherer story worlds: they are signposts that point to important details in the stories, and are key to unlocking the knowledge they encode.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

“In some sense repetition operates like the chorus in Western drama, serving to reinforce the theme and to focus the participants’ attention on central concerns, while intensifying their involvement with the enactment.”

—Allen (1983:11)

Photo by Ann Sugiyama Gardner

Distant Time

Many characters in hunter-gatherer stories are anthropomorphized natural phenomena, such as animals, trees, rivers, mountains, stars, and winds. Stories that feature these hybrid beings are set in Distant Time. Most forager cultures make a distinction between the distant and recent past. The latter is equivalent to history, while the former is an era long ago when the world was different than it is today, and things occurred that are no longer possible. Although humans in their present form did not yet exist, the world was populated by beings that had the capacity for speech and other human qualities. Forager storytellers often refer to this era as “the time when the animals were people.” Distant Time ended when a great period of Transformation occurred, during which these beings acquired their present form.

“the oral tradition . . . exists in a dimension of timelessness.”

—Momaday (1976:ix)

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Distant Time stories typically use formulaic openings and closings–standard lines or expressions used to begin and end a tale. These formulae signal that the events being recounted transpired during the Distant Time era. These stories typically begin “Long ago” or “In the beginning,” but closings vary widely. For example, the Koyukon people of Alaska have a tradition that telling these stories shortens the winter. Thus, a Koyukon narrator commonly ends a Distant Time story by saying, “I thought that the winter had just begun and now I’ve chewed off a part of it” (Attla et al. 1983).

The concept of Distant Time is not unique to foragers. Many European fairy tales and legends take place in an era long ago when things occurred that are no longer possible. Like Distant Time stories, many of these narratives use formulaic openings and closings, such as “Once upon a time” and “They lived happily ever after.” Modern fantasy tales often use the same device—for example, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.”

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

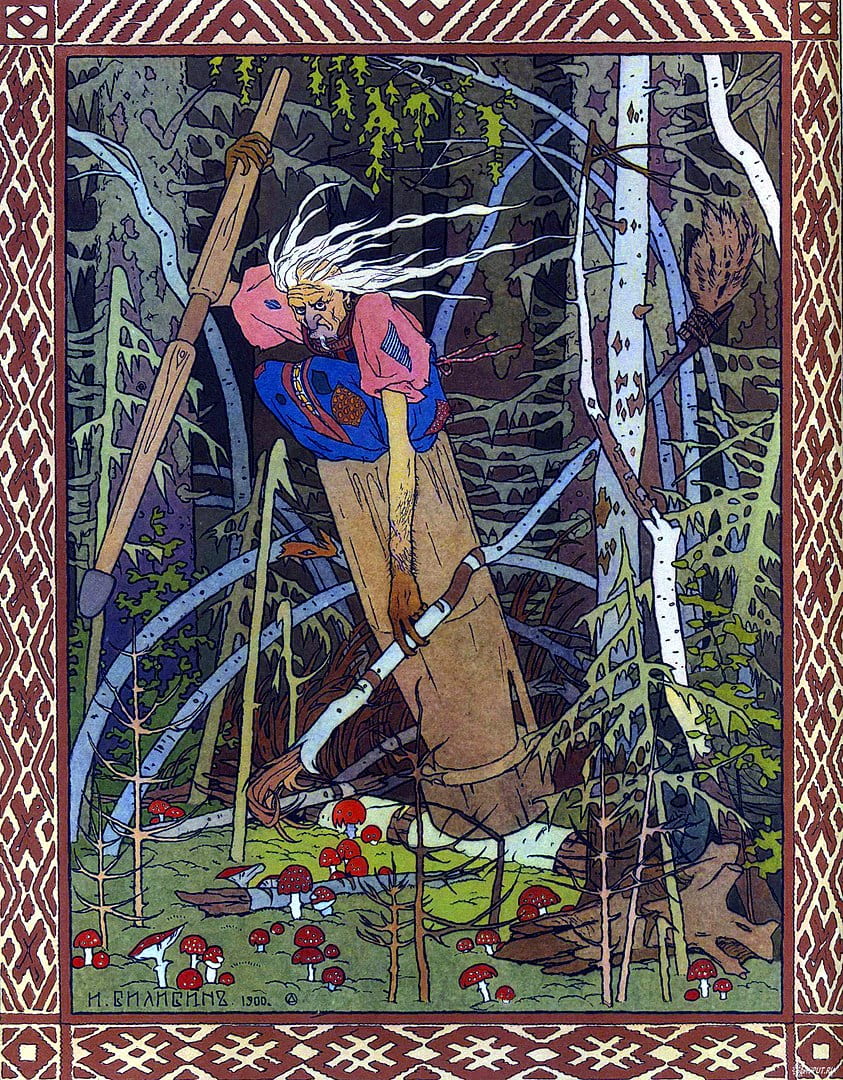

Distant Time stories commonly feature anthropomorphic or zoomorphic beings with supernatural powers, such as the ability to shape-shift or transform the natural world:

Genres

The natural world is a recurrent subject in hunter-gatherer storytelling

Etiological Tales

Many of the stories set during the Transformation era are etiological tales. These are narratives that explain how things came to be: how a river acquired its winding course, why a certain plant fruits in winter, why warm winds blow in early spring. In so doing, these stories provide useful information about the local environment. Etiological animal tales are a case in point: in the course of explaining why the emu is fleet, why mountain sheep live on rocky cliffs, why birds migrate in winter, why obsidian is used to kill deer, and so on, these stories describe hunting techniques and species traits. This is precisely the type of information that foragers use to plan their forays, and to locate, stalk, and catch fish and game. In the words of Gwich’in Elder Mary Kendi, “The stories were interesting as we learned about the animals that we depended on and shared the land with. We also learned how to hunt the animals, what time of the year, the best locations, and the best ways to hunt” (Gwich’in Elders 1997:17).

“‘we have a long history of sharing our knowledge about the land and animals. . . . By telling the stories, the Elders and our parents were able to pass on their knowledge and the knowledge of our ancestors.'”

–Gwich’in Elder Mary Kendi (Gwich’in Elders 1997:17)

Animal tales provide information about habitat,

markings and morphology,

locomotion and vocalizations,

sensory systems, mating, and life history.

Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Telling the Hunt

Hunter-gatherer storytelling includes personal experience narratives. Among the most popular are hunting stories, known in anthropology as “telling the hunt.” These are accounts of actual hunting experiences or encounters with dangerous animals, and typically feature detailed descriptions of animal behavior and vocalizations, as well as hunting techniques. Personal experience narratives are not limited to animal encounters: they address other challenges of forager life, such as famine, inclement weather, natural disasters, and warfare.

“A very common topic of conversation while lying in their hammocks at night will be a relation of the day’s doings . . . with details of almost scientific precision. . . . The narrator will give particulars, step by step, of the route taken, the creeks crossed, the trees seen, the bird and animal life noted, the persons met, what he and they said and did, and everything else that was noticed, however ordinary or matter-of-fact it might be.”

—Roth (1924:483)

Science Fiction?

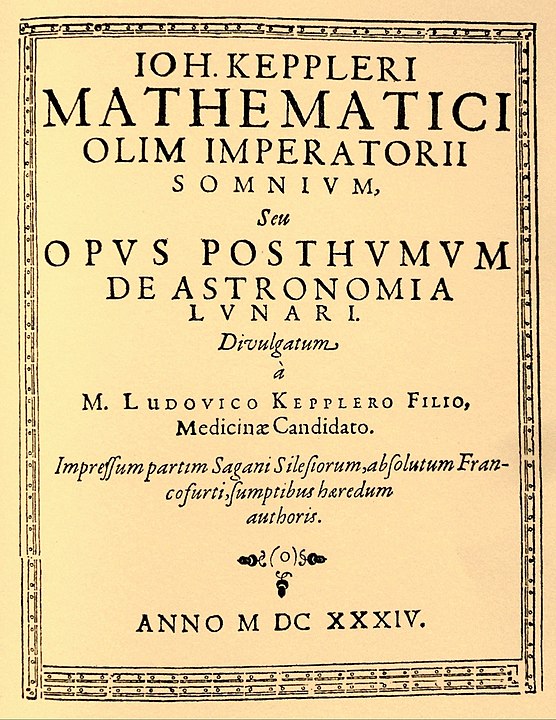

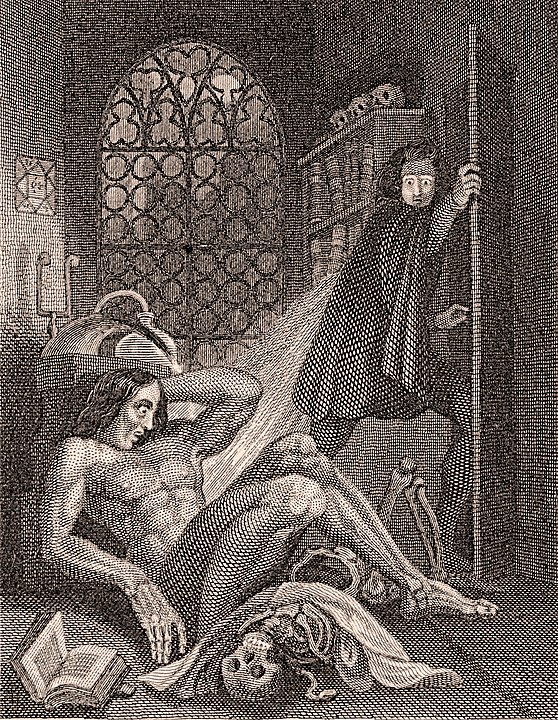

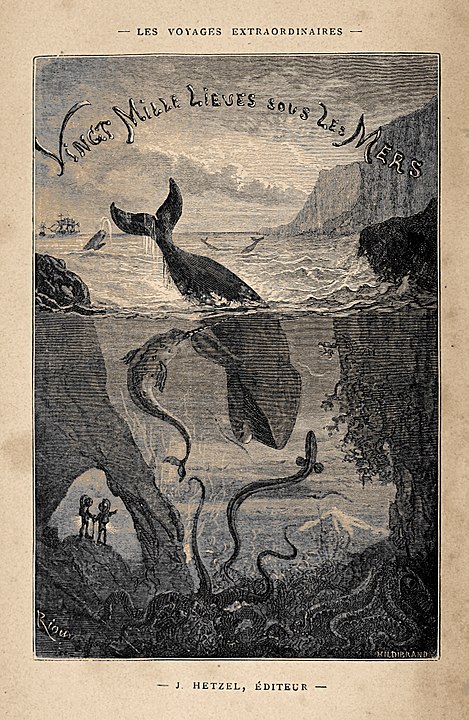

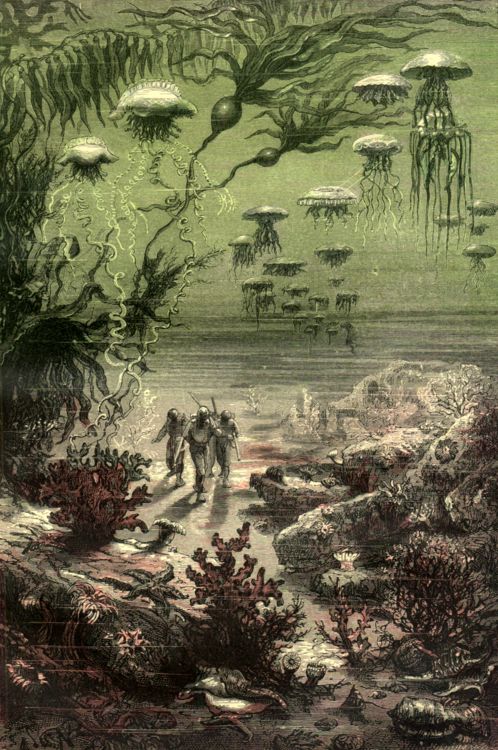

The science fiction genre is often perceived as a modern development. Some situate its emergence in the Enlightenment period, with the publication of such classics as Kepler’s Somnium (1608) and Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726). For others the birth of this genre is associated with more recent works, such as Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) and Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas (1869). For still others, the term “science fiction” conjures up images of spaceships, teleportation, and lightsabers—technologies that are not typically associated with hunter-gatherer life. However, the roots of science fiction lie in forager oral tradition.

Somnium by Johannes Kepler

Frontispiece of Frankenstein by Theodor von Holst

This can be seen by interrogating Western definitions of the genre. Some definitions are unnecessarily narrow. For example, Asimov describes science fiction as “that branch of literature which deals with the reaction of human beings to changes in science and technology.” This view underplays the speculative current pulsing through the genre, envisioning the twists and turns that science and technology might take in the future (e.g., Frankenstein, WALL-E ) or might have taken in the past. Examples of the latter include the Star Wars film series, the 2004 tv series Battlestar Galactica, and the “Time and Punishment” episode of The Simpsons Treehouse of Horror series.

Somewhat less problematic is the definition provided by The Literature Book, which characterizes science fiction as “scenarios that are at the time of writing technologically impossible, extrapolating from present-day science.” The reference to writing would appear to exclude oral cultures. However, if we take “at the time of writing” to mean “at the time of creation” the definition becomes more inclusive. On this view, science fiction depicts scenarios that are technologically impossible in their culture of origin at the time they are produced. This modified definition acknowledges that science and technology vary from culture to culture, and that the term science fiction is therefore a relative one.

Cover illustration by Alphonse de Neuville & Édouard Riou

At the other end of the spectrum, some experts, such as Lester del Rey and Damon Knight, argue that the science fiction genre resists delimitation. However, there is general agreement that this genre treats subjects such as science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life. In line with this view, some experts argue that Lucian’s A True Story, written in the second century AD, can be classified as science fiction because it features travel to outer space, alien lifeforms, and interplanetary warfare. By virtue of their references to similar phenomena, many forager narratives can be considered science fiction as well.

For example, Nuxalk oral tradition includes stories about a monster called the snɩnɩq that kills by shooting powerful beams of light from its eyes. This trait anticipates fantastical weapons depicted in Western science fiction, such as ray guns and lightsabers, as well as real-world laser technology. Similarly, the Jicarilla tell of a giant monster elk that had half human blood and “was able to transfix the people with his eyes and they couldn’t run away when he looked at them. So they would stand immovable, and he would come up and kill them” (Opler 1938:58-59).

Monster elk? | Photo by Codex

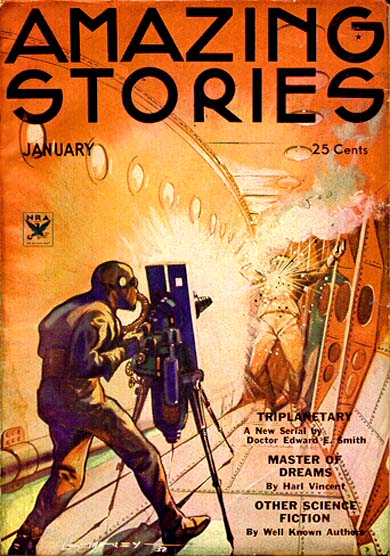

Ray gun | Illustration by Leo Morey

The snɩnɩq uses its eyes like a ray gun:

“this monster. . . . is regarded as being about the size of a large grizzly bear, but with long front legs and short hind ones, on which it can run in upright position. . . . Its legs terminate in large talons resembling those of an eagle, with the thumb set opposite to the fingers; its pelt, long and fleecy, is of a grayish-blue colour. The monster is able to roll its eye-balls completely over, and, when the reverse side is exposed, there shoot forth dazzling beams of light which strike senseless anyone on whom they fall. It uses its eyes for hunting.”

—McIlwraith (1948:435)

Warp drive | Image by Alorin

“Killer-of-Enemies asked help from the sun. When something shiny is held up it throws a gleam of light and that light travels as fast as eye can see. ‘Let that be my legs,’ Killer-of-Enemies asked. And Sun said, ‘All right.’ Then he. . . . [began] running for his life. At first Killer-of-Enemies used his eyes. He fixed his gaze on a distant mountain and as soon as he saw it, he was there. Then he looked to another, and as his glance fell on it he was already there. He continued to do this until his eyes got tired.”

—Opler (1938:70)

Forager oral tradition also references teleportation. The adventures of the Jicarilla culture hero Killer-of-Enemies are a case in point. In one of these adventures, Killer-of-Enemies is pursued by two huge running rocks that have been killing people. When he realizes that he can’t outrun them, he asks his father the Sun for help. The Sun helps him by enabling him to travel at the speed of light. The story’s description of this event is scientifically cogent and shows that the concept of light speed is not limited to Western cultures: “he began to use the speed of light which the sun had promised him. The sun would throw a beam of light ahead and he would travel with it to that place” (Opler 1938:71). Killer-of-Enemies’ use of this tactic anticipates warp drive, the fictional Western technology popularized in the Star Trek series. It also presciently echoes the scene in Star Wars (1977) in which space pilot Han Solo escapes attacking stormtroopers by accelerating to light speed. In another part of the story, Killer-of-Enemies uses the power of thought for teleportation: “He would think of some distant place which lay ahead, and as soon as he thought of it he would be there” (Opler 1938:70-71).

Forager narrative also includes stories about alien lifeforms. For example, the Tehuelche of Patagonia tell of people who live on the sun. Also, many stories describe encounters between humans and extraterrestrial beings. For example, the Wichí of the Gran Chaco tell of a man who married a star: “Every night the star-woman would leave her home in the heavens, visit her lover, and then return. . . . Finally . . . [she] took him to the sky with her as her husband” (Wilbert & Simoneau 1982:47).

Photo by MjolnirPants

“High above the firmament live the people of the sun. They eat as we eat. But we eat and defecate, and they do not. They are like owls. They eat and eat and eliminate through the mouth. . . . They only have that with which to urinate and to have offspring, but the part for defecation is closed.”

— Wilbert & Simoneau (1984:20)

As seen in a myth from the Chewong of Malaysia, human-extraterrestrial marriages don’t always work out:

“Once a star came down from the sky. She went to Bongso’s house. They slept together and became man and wife. . . . They passed a rotten tree full of maggots. The wife asked Bongso to kill the maggots, but he said to eat maggots is dirty. . . . ‘I do not want you, and you do not want me,’ she said to Bongso, and then she returned home to the sky using the smoke as her path.”

—Howell (1984:109)

Photo by Karla Kenny

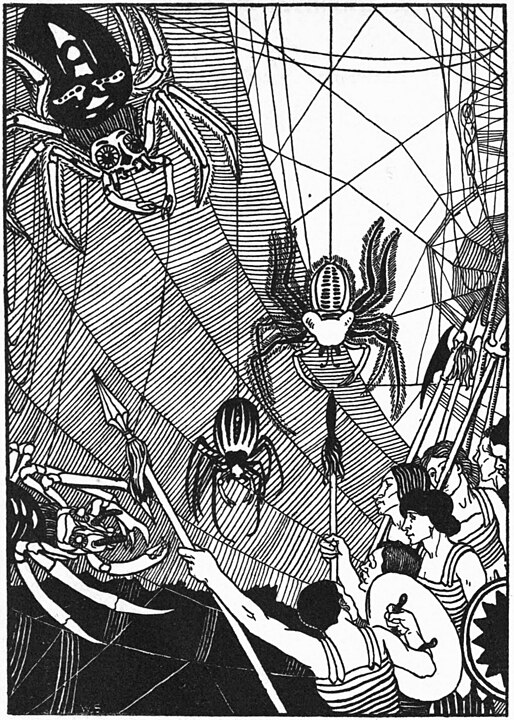

Spider battle scene from Lucian’s A True Story

In other cultures, the reverse occurs, with women traveling to the sky world and marrying star husbands. For example, a Quinault story tells of two young women who are teleported to the sky by the power of thought, and find themselves married to star men. The younger girl is unhappy with her star husband, so she runs away. She comes upon Spider, another denizen of the sky world, who is making rope. In a scene which anticipates modern thought on the potential applications of spider silk, the girl begs Spider to let her use the rope to return to earth. Later in the story, the Earth People make war on the Sky People in order to recover the other sister. Thus, like Lucian’s A True Story, this tale includes travel to outer space, alien lifeforms, and interplanetary warfare.

Star husband tales have been documented in at least 29 Native cultures across North America, from the Pacific Northwest and the Great Plains to the Great Lakes and Nova Scotia. The version told by the Quinault people is representative:

“Once Raven’s two daughters went out on the prairie to dig roots, and night came on before they knew it, so that they had to camp out where they were. And as they lay talking under the open sky, they came to speak of the stars; and the younger girl said, ‘I wish I were up there with that big bright star!’ and the older said, ‘I wish I were there with that little star!’ Soon they fell asleep, and when they waked they found they were up in the sky country, where the stars are; and the younger girl found that her star was a feeble old man, while the elder sister’s star was a young man.”

—Farrand (1902:107)

To rescue the older girl, the Earth People make an arrow chain. As the story explains, Wren and Snail embedded an arrow in the sky, then “shot arrow after arrow, and each stuck in the notch of the one preceding, and made a chain reaching down to the earth” (Farrand 1902:108). The arrow chain motif is another example of futuristic or “impossible” technology envisioned in forager narrative. This motif has been documented in the Americas, Melanesia, and East Eurasia.

A Trip to the Moon | By Georges Méliès

In an Ainu story about a trip to the moon, the hero travels by means of an arrow ladder:

“My elder sister brought me up. . . . Once she went out and I waited for her in vain. . . . [I] went to my grandmother the Willow-Bush Thicket, and asked her; and she said. . . . ‘Thy sister went up to the moon, and got married to the Man in the Moon.’ I got very angry and. . . . took an arrow with a black feather, and another one with a white feather, and went out. First I let fly the arrow with the black feather, then the one with the white feather, and, holding the ends of the arrows with my two hands, I rose up into the air among the clouds.”

—Pilsudski (1912:73-74)

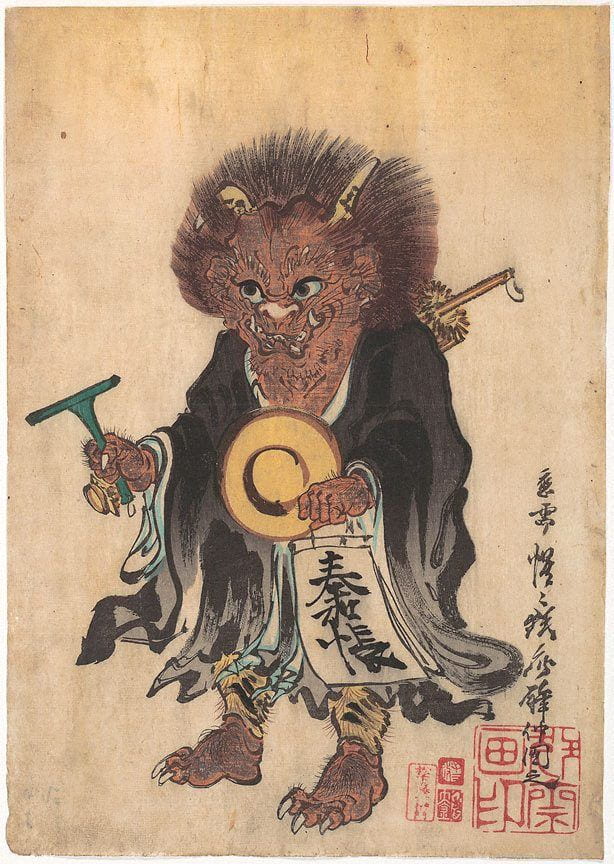

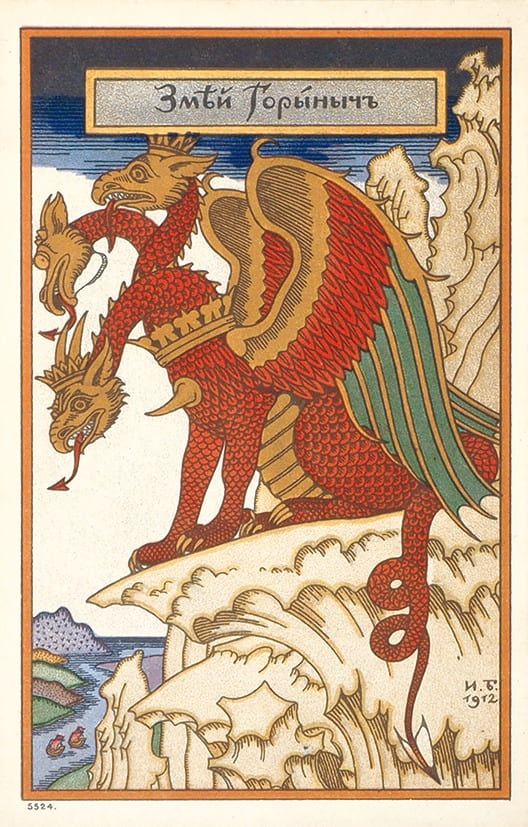

Image by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

Forager oral narrative also includes stories about giant animals (e.g., the monster elk) that terrorize humans. These stories are similar to the kaiju (“strange beast”) subgenre of science fiction inspired by the character King Kong and ushered in by the film Godzilla in 1954. In their twentieth-century incarnation, kaiju are typically depicted as attacking cities. However, this term originally referred to monstrous creatures from ancient Japanese legends, such as dragons. Monsters that attack humans or their settlements are common in forager folklore. The Bororo, for example, tell of a “monster named Butoríku, who resembled a huge snake, often attacked the Bororo, carried his victims off to his cave, and greedily devoured them” (Wilbert & Simoneau 1983:138). This brings us to another common genre in forager oral tradition . . .

Monsters

Stories about monsters are common in world folklore generally, despite the fact that humans have never been vulnerable to predation by such creatures. Key to understanding this phenomenon are the real-world threats that monsters represent: these beings are typically associated with hazardous locations, such as dense forests, rugged mountains, whirlpools, or swamps. Although dangerous, these threats are inanimate and passive. In contrast, monsters are sentient, capable of self-locomotion, and have the goal of harming humans. Thus, because they have agency, monsters are more likely to engage evolved alarm systems such as our predator-evasion psychology. For this reason, characterizing a topographic feature as the home of a voracious ogre may make it seem more threatening.

“In the lowland floodplain waters lived the Foggy Men, man-eating monsters whose emergence was marked by swirling eddies and the fogs and mists rising from the marshes.”

—de Laguna (1995:301)

Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Depiction of an oni monster by Kawanabe Kyōsai

Like predatory animals, monsters tend to have a large powerful body, strong jaws, big sharp teeth, long sharp claws, forward-facing eyes, and keen sensory systems. They often have thick hide, fur, or scales, making them difficult to kill, and they tend to be capable of rapid locomotion, making them difficult to evade. Some also have armaments, such as horns or a supernatural power, that make them even more menacing. Their modus operandi is to haul their victims off to a lair deep in the wilderness, often stuffing them into a basket that they carry on their back. As this habit suggests, monsters also tend to be anthropomorphic, exhibiting opposable thumbs, bipedal locomotion, speech, and/or human cognition. Thus, monsters embody the physical advantages of predatory animals, and the ingenuity and Machiavellian intelligence of humans: monsters are a mash-up of traits that make them very good at killing.

This may explain why we find monsters so compelling, despite the fact that they do not pose a threat in and of themselves. The popularity of dragons is instructive here: the anthropologist David Jones attributes their pervasiveness in world folklore to their hybrid nature. By combining salient characteristics of three major primate predators–raptors, snakes, and felids—dragons reference multiple sources of danger. Similarly, with their combination of animal and human traits, monsters evoke two adaptive problems simultaneously: predator evasion and human aggression. Thus, like dragons, monsters may engage multiple threat-detection systems, making them highly attention-getting.

“When I used to play with my little friends . . . if we strayed near the woods, someone was always sure to warn us that the Double-face might get us. Nobody knew what that was, but we were all afraid of it.”

—Deloria (1932:50)

Photos by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

These characteristics make monsters well suited to discouraging children from engaging in dangerous activities. Children are more vulnerable than adults to a host of threats, including injury, poisoning, exposure, drowning, animal predation, and abduction. They are also more prone to getting lost, which exacerbates these risks. Children’s vulnerability is rooted in their lack of experience, compounded by their curiosity and tendency to discount danger: one by-product of being a highly intelligent animal designed for learning is that children are very curious about their environment and highly motivated to explore it.

“A small child cannot survive long in the Paraguayan forest, and if not found within one day is unlikely to survive.”

—Hill & Hurtado (1996:222)

This poses a problem for parents: it is impossible for them to supervise their offspring continuously, and children do not always heed parental warnings. Associating inanimate hazards with a threatening agent may make them more frightening to children, increasing the likelihood that they will avoid them. Tellingly, stories about monsters that target disobedient children are common in forager oral tradition. Ethnographic accounts report that these stories are told to children to discourage them from engaging in behaviors that might expose them to danger, such as crying, playing outside at night, wandering off alone, or frequenting dangerous places.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

“The people of long ago did not want their children to play outside when it became evening, because possibly some dangerous thing might mingle with them. That is why they did not want them to play outside. Perhaps a wild person of the woods might steal (enslave) them. That is why just as evening approached they took in their children at that time, for they feared various things.”

–Coos Elder Annie Miner Peterson (Jacobs 1939:82)

The association of dangerous places and activities with monsters may also exploit our social referencing psychology. Social referencing is a process whereby infants and young children use adults’ emotional reactions to make sense of an unfamiliar or ambiguous entity—for example, to determine whether the entity is dangerous. This phenomenon was documented in a set of “visual cliff” experiments, in which an infant was placed on one end of a table while its mother stood at the opposite end and played with an attractive toy, encouraging the infant to crawl toward her. When the infant reached the middle of the table, it encountered what appeared to be a drop-off and looked to its mother’s face for guidance. When mothers displayed a happy expression, most infants continued crawling beyond the “cliff” but when mothers displayed a fearful expression, the infants stopped. A practical use of this phenomenon is the application of Mr. Yuk stickers to toxic household products, such as laundry detergent, to discourage children from ingesting them. Mr. Yuk’s facial expression serves as a proxy for that of the parent, informing or reminding the child that the entity in question is unsafe. Monster stories may similarly communicate information about adult emotional attitudes toward certain stimuli. Provided that they make a lasting impression on the child’s memory, these stories can be referenced when the parent is absent.

“As a means for the control of conduct there is no measure more used or more successful than the telling of a myth. If a child is unruly at night, the story of the monster owl and his basket is enough to force quiet and obedience.”

—Opler (1938:xii)

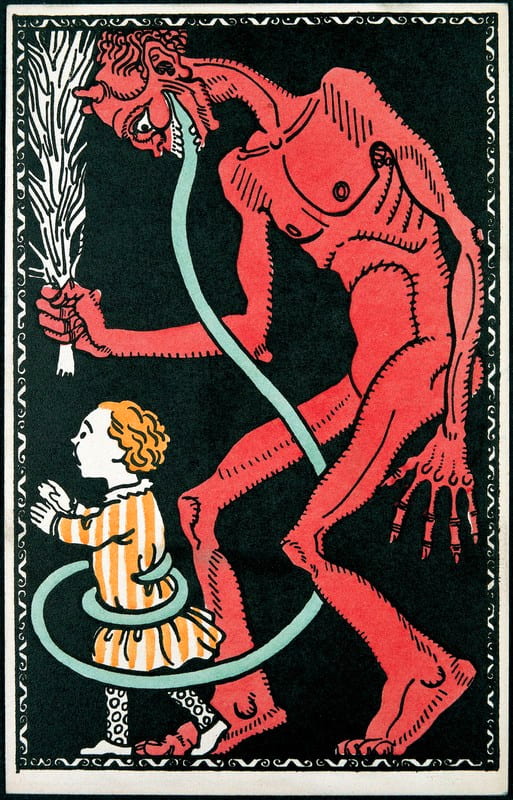

This parenting strategy is not unique to foragers. In the alpine regions of Europe, for example, children were warned to beware of the Krampus, an anthropomorphic being with horns, fangs, cloven hooves, a pointed tongue, and a hairy body who accompanies Saint Nicholas on his annual visit. Together, they constitute a disciplinary duo: Saint Nicholas rewards good children with treats, while Krampus threatens naughty children with a bundle of birch branches.

Krampus postcard | Image from Wikimedia

Krampus greeting card | Image from Wikimedia

In diverse habitats and cultures across the globe, monsters are associated with dangerous places, activities, and/or conditions: