Cumulative culture depends not only on evolved cognitive capacities (e.g., shared attention, shared intentionality, social referencing, and language), but on access to suitable learning opportunities. The problem is, such opportunities might not occur by the time they are needed. Humans are able to bypass this problem through application of their innovative and instrumental intelligence: their abilities to reason counterfactually and causally enable them to imagine and engineer “adaptively structured learning environments”—that is, to create timely, tailored learning opportunities when naturally occurring opportunities are lacking, impractical, or dangerous.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

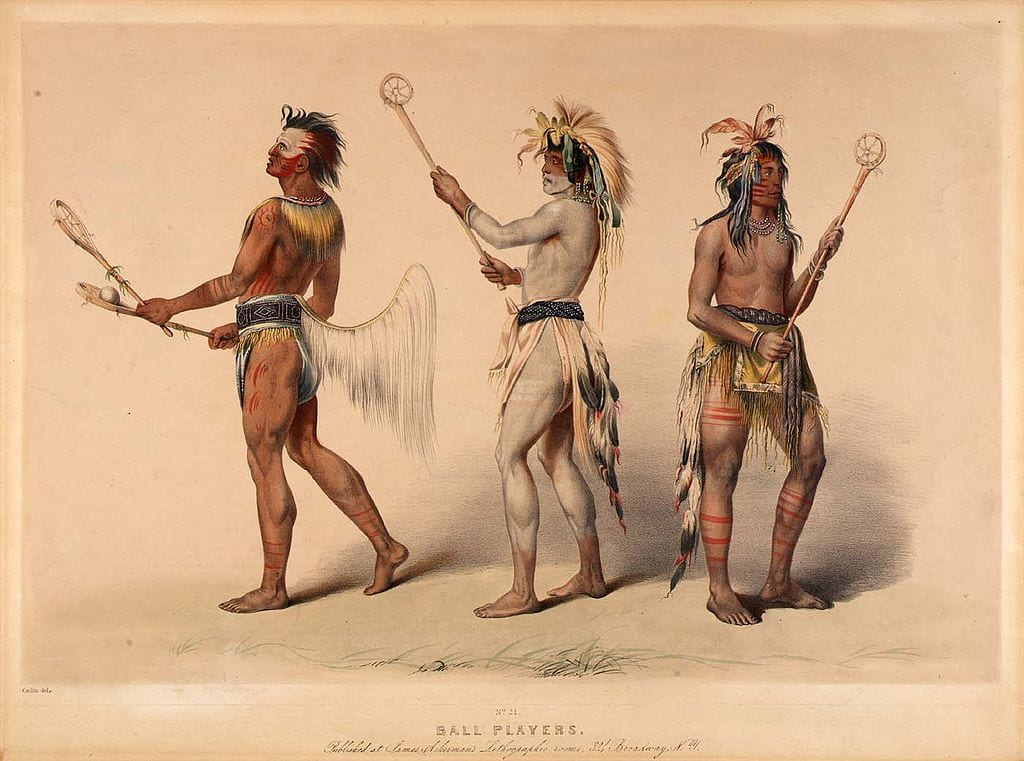

“Ball-play of the Choctaw—Ball Up” by George Catlin

In hunter-gatherer societies, what options are available for creating structured learning opportunities? Games are one obvious candidate but have been largely overlooked in teaching taxonomies, perhaps because they are a form of play. While play behaviors (e.g., play fighting, chase play, object play) are widely believed to develop skills needed later in the lifespan, they are almost certainly adaptations and thus not human inventions.

Games, however, are not mere play: games are play activities characterized by competition, two or more sides, criteria for determining the winner, and agreed-upon rules. Moreover, they are often suffused with symbolic resonances, and involve pretense and role-playing. On this view, games are human inventions: they are constructs made up of rules and imaginative frameworks, which are superimposed on innate play behaviors.

Mapuche game of chueca by Alonso de Ovalle (1646)

“Children Throwing Snow Balls” by William Ward (1785)

“A Football Game” by Thomas Webster (1839)

Children playing Red Rover

One possible benefit of such constructs is that they can be used to guide play activities in ways that increase their pedagogical efficaciousness. For example, coalitional play fighting (e.g., snowball fights) occurs spontaneously, but mock warfare games exhibit rules–e.g., “When four of a side are hit, it is the end of the game” (Opler 1946:76-77)–that simulate certain conditions of lethal raiding. Forager raiding parties commonly comprise fewer than twenty men; thus, a loss of four might reverse the intergroup power differential and make immediate retreat (i.e., ending the attack) the most prudent course of action. Team games can provide a visceral reminder and demonstration of this principle. A Coeur d’Alêne game called “making slaves” focuses on another aspect of warfare. This variant of tag appears to simulate counting coup and evading capture: players sought to touch the hand of a member of the opposing team, then return to their own team’s lines without being caught. Anyone caught was “called a ‘slave’ or ‘captive of war,’ and was conducted over to the enemy lines by the person who caught him” (Teit & Boas 1930:134).

Rules and imaginative frameworks may also be used to tailor play activity to local constraints, challenges, and/or affordances. The wolf game, played in many Inuit societies (e.g., Rasmussen 1930, 1931, 1932), is a case in point. In this game, one or more players are wolves, and the rest are humans attempting to escape the wolves. The predator-prey framework reminds players of a very real threat, and encourages them to “think like a wolf”—to think about how wolves attack, and what humans can do to evade them. In a variant, some players are wolves and others are caribou. This framing calls attention to an important interspecies relationship, and encourages players to think in terms of how each species reacts to the moves of the other. Contingent inter-species behavior is among the ecological cues used by foragers to locate game; thus, play that calls attention to such behavior may help build players’ encyclopedia of local zoological knowledge.

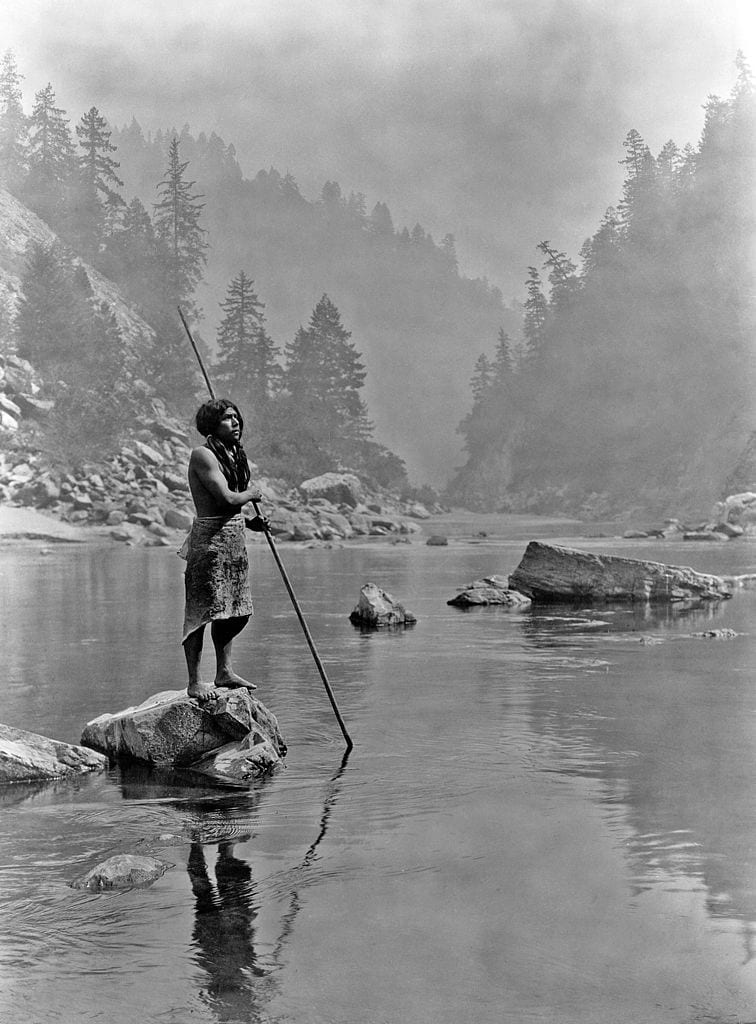

Photo by Joe Robertson

Kayakers and sea otters | Photo by Brocken Inaglory

Aleutian image depicting sea otter hunt | Photo by Ляпунова Р.Г.

The aiming and throwing of projectiles is another widespread form of amusement that develops spontaneously and has obvious fitness benefits, but exhibits cultural modifications that appear to calibrate it to local ecological conditions. Some of the most compelling evidence of this is the presence of multiple target-shooting games within a given culture, each of which appears to be tailored to develop a subset of the skills demanded by projectile weapon use or by pursuit of a certain game type. Chugach men, for example, played at least two different shooting games. One of these, which provided practice for sea otter hunting, involved two ten-man teams who “stood in two parallel rows pointed to the target, so that the men at the far ends of the rows had to shoot up in the air to avoid hitting their team mates” (Birket-Smith 1953:105). Chugach men also played a variant of hoop-and-pole, in which players take turns trying to throw an arrow or spear through a rolling hoop. This widespread game (Cooper 1949:505, 508; Culin 1907; Thomas 2007:61) appears to provide practice for hitting low-lying targets.

The Eastern Cree, too, had several different shooting games, each targeting a different species and age group (i.e., skill level), and employing different weaponry or tactics. In the Otter Hunting Game, two men competed to hit ten wooden otters, each smaller than the other. The winner was the man who hit the smallest otter, which was kept moving with a stick. In the Caribou Hunting Game, small boys shot rocks or arrows at a target carved to resemble a caribou. In the Goose Hunting Game, played by older boys, the “hunters” stationed themselves behind a blind and used sticks to sling rocks at feathers held by their playmates, who approached from different directions (Skinner 1911:37-38).

Snow geese (Anser caerulescens) | Photo by Steve Hinshaw

Staff slings used to hurl rocks (upper right)

Other projectile-based games appear to be specialized for warfare. For example, the Eastern Cree played a game in which blunted arrows were aimed at a player who ran back and forth, attempting to avoid being hit. This game was played by men and boys “to teach dexterity in dodging missiles, a necessary part of a warrior’s education” (Skinner 1911:37). The Netsilingmiut played a similar game in which players threw stones at each other and tried to dodge them; players who got hit were “dead” and out of the game (Rasmussen 1931). Collectively, a group’s shooting games appear to provide practice at a variety of tasks: hitting stationary vs. moving targets; aiming at species that differ in size, morphology, and locomotion; using different types of projectile weapons; shooting from cover vs. from an exposed position; and dodging.

Racing games are also frequently mentioned in the forager ethnographic record, and exhibit a range of specializations. The Yukaghir, for example, had races on foot in summer and on snowshoes in winter (Jochelson 1926:129). The Jicarilla Apache had both speed and endurance races, as well as different ways of starting them. For example, in some races the runners started from a stooping position, while in others “the runners lie down flat, face up. Then they are given the signal to go. If a man is slow in rising, he loses ground” (Opler 1946:82). In other races, handicaps were imposed on participants. For example, in one race players had to run backwards; another required them to run on all fours like horses; and yet another required them to “put one hand down to one leg and keep the other hand and leg off the ground” (Opler 1946:82). The Jicarilla also had several types of relay races. In “they carry a rabbit,” each team had to carry a stuffed rabbit to the finish line; if the carrier got tired, he would hand the rabbit off to a teammate. The Ge-speaking peoples of Brazil had a relay race in which male adolescents and adults carried logs weighing up to 200 pounds (Cooper 1949:508).

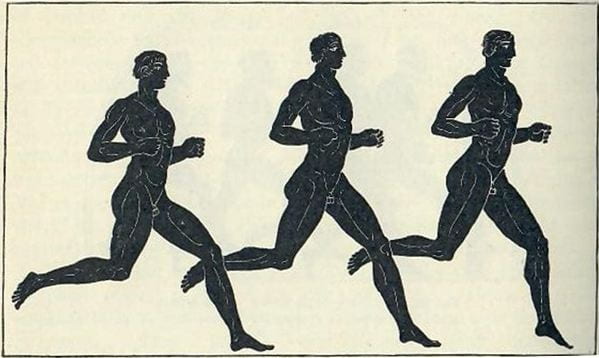

Ancient Greek long-distance runners (c. 333 BCE) | Photo by Ricky Bennison

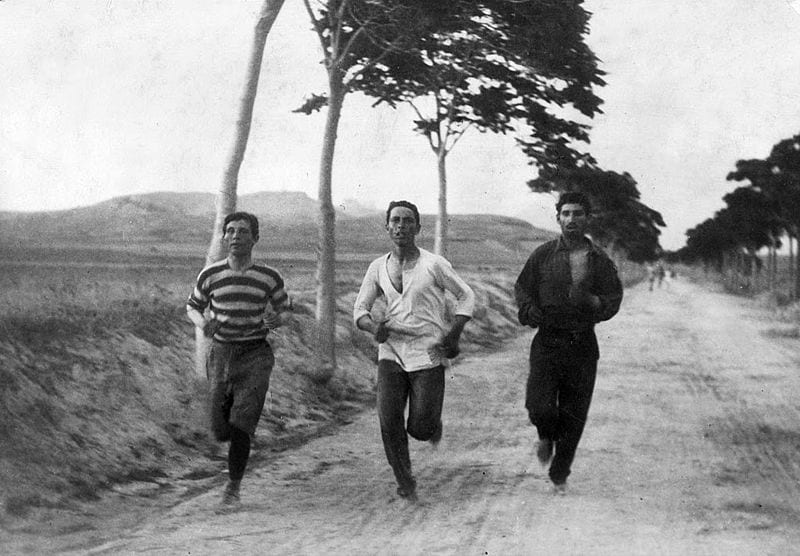

Three athletes on the road from Marathon training for the 1896 Athens Olympic Games | Photo by Burton Holmes

Photo by Brian Erickson on Unsplash

Some racing games exhibit imaginative framings that appear to reference warfare. A Jicarilla girls’ race, for example, is played with a stuffed squirrel skin that represents a baby. One runner on each team carries the “baby” in a blanket “just as an Indian mother does. If she runs too fast the squirrel may fall out. One picks up the ‘baby’ if the other loses it. The one who returns to the starting point first with the ‘baby’ wins for her side” (Opler 1946:83). Other Jicarilla races involved running to the top of a hill or mountain and back. In addition to developing stamina, distance races may have helped prepare children for emergencies by familiarizing them with the local terrain–especially escape routes, vantage points, and hiding places. As one informant explains, “Before a fight the people agree on a place to meet if they have to scatter. They tell the children the names and locations of the mountains and tell them to gather at the appointed place if they get lost or are chased” (Opler 1946:84).

Ethnographic reports on the training of young people explicitly link games with practical skill acquisition. Among the Mbuti, for example, elders frequently “called the children into the main camp and enacted a mock hunt with them there. Stretching a discarded piece of net across the camp, they pretended to be animals, showing the children how to drive them into the nets” (Turnbull 1983:44). In southeast Australia, boys engaged in sham battles using clubs and shields. According to Worsnop, “The object in all these games was to instruct the young in the arts cultivated by the fighting men of the tribe and to gain expertness in the use of the weapons, so as to obtain food with certainty and wield them with advantage in the tribal wars” (1907:167). Similarly, a Jicarilla informant reports that, “When there are many camps together, they make the boys train together and race against each other. . . . They are made to wrestle with one another” (Opler 1946:87). The Jicarilla clearly saw racing as preparation for hunting and warfare. A father might exhort his son by telling him, “If you are a good runner, it serves you well for the hunt. You can go out and succeed at hunting deer,” and “Some day when the enemy runs after you on horseback, you will leave them behind, even though they have good horses” (Opler 1946:86).

Thus, although game play in hunter-gatherer societies might largely appear to be a combination of self-directed and peer-to-peer learning, much of it was encouraged and scaffolded by adults. One clear cut form of support was the manufacture of miniature tools and weapons. For example, Yamana fathers made small bark canoes for their daughters, who as early as the age of seven were capable of managing them on their own and following behind their mothers on fishing trips (Gusinde 1937:584). Boys were given “imitations of the weapons and tools that the men use on their hunts,” and were encouraged to engage in various athletic competitions, such as archery contests: “boys are lined up not far from the target and must demonstrate their aim. They are praised or scolded according to their accomplishments” (Gusinde 1937:579). Gusinde adds that, although children often damage or lose the implements their parents provide them, “adults never tire of making replacements” (1937:579).

In sum, the ethnographic record indicates that forager adults actively scaffolded children’s game play by providing encouragement, criticism, and instruction, as well as equipment and occasions dedicated to this activity. Thus, games appear to comprise various behaviors classified as teaching in current taxonomies: evaluative feedback, opportunity provisioning, and direct active teaching. Furthermore, evidence points to a pedagogical motive behind this scaffolding: adults encouraged children and adolescents to participate in certain games as a means of training them for tasks they would face in adulthood. Clearly, games are educational human inventions and thus warrant consideration as adaptively structured learning environments.

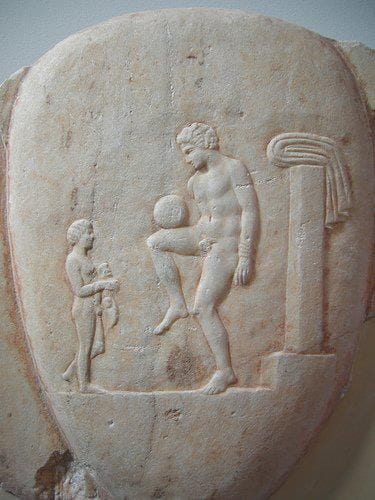

Ancient Greek football player

Birket-Smith, K. (1953). The Chugach Eskimo. København: Nationalmuseets publikationsfond. Retrieved from http://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu.libproxy.uregon.edu. Accessed May 29, 2020.

Cooper, J. (1949). Games and gambling. In J. Steward (Ed.), Handbook of South American Indians, Vol. 5. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 503-524.

Culin, S. (1907. Games of the North American Indians. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Gusinde, M. & Schütze, F. (1937). The Yaghan: The life and thought of the water nomads of Cape Horn. In Die Feuerland-Indianer [The Fuegian Indians], Vol. II. Retrieved from http://ehrafworldcultures.yale.edu.libproxy.uoregon.edu. Accessed June 5, 2020.

Jochelson, W. (1926). The Yukaghir and the Yukaghirized Tungus. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. 9, Parts 1-3. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Opler, M. (1946). Childhood and Youth in Jicarilla Apache Society. Los Angeles: The Southwest Museum.

Rasmussen, K. (1930). Intellectual culture of the Hudson Bay Eskimos, Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 1. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Rasmussen, K. (1931). The Netsilik Eskimos: Social life and spiritual culture, Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 8. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Rasmussen, K. (1932). Intellectual culture of the Copper Eskimos. Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 9. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Roth, W. (1897). Ethnological studies among the north-west central Queensland Aborigines. Brisbane: Edmund Gregory.

Skinner, A. (1911). Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, 9, 1-178.

Teit, J. & Boas, F. (1930). The Salishan tribes of the western plateaus. In 45th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, pp. 25-395. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Thomas, M. (2007). Culture in Translation: The Anthropological Legacy of R. H. Mathews. Acton, Australia: ANU E Press.

Thomas, N. (1906). Natives of Australia. London: Archibald Constable and Company, LTD.

Turnbull, C. (1983). The Mbuti Pygmies: Change and Adaptation. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Worsnop, T. (1897). The Prehistoric Arts, Manufactures, Works, Weapons, etc. of the Aborigines of Australia. Adelaide: C. E. Bristow, Government Printers.