Hunter-Gatherer Chase Games

Michelle Scalise Sugiyama | November 23, 2024

“Most play is chasing and play fighting. These are the two most fundamental kinds of play, ‘bread and butter’ play, so to speak.”

—Aldis (1975:11)

Run for your life!

Play behaviors are hypothesized to be developmental adaptations that hone and calibrate skills needed later in the lifespan. One of the most common forms of locomotor play — in both humans and non-human animals — is chase play. This behavior evokes the adaptive problems of predator evasion, hunting, & conspecific aggression. It consists of one party pursuing another party and trying to catch them, while the pursued party attempts to evade capture. In humans, chase play is typically elaborated into games, such as tag and hide-and-seek. These are structured activities that feature rules, turn-taking, and imaginative frameworks.

“This is often played by children. It is precisely the ordinary game as we know it, the object being merely for one to run after and touch another. In doing so, he cries ‘a·mak,’ and hence the name a·makitaujuᴀrnᴇq, which means ‘to say a·mak to one another.’”

—Rasmussen (1930:244)

Basic Tag

Tag games are also referred to as “touch” and “catching” games. In its simplest form, tag requires only two players, but most tag games involve group play. In some forms of group tag only one person does the chasing, while in others there are multiple chasers. The first type of group tag is illustrated in the game a·makitaujuᴀrnᴇq, played by the Hudson Bay Inuit.

Imaginative Frameworks

Many tag games feature a pretend component. These imaginative frameworks reference activities in hunter-gatherer life that involve chasing or being chased, such as predator evasion. This is illustrated in another Hudson Bay Inuit game called “The Wolf Game,” in which the person who is “it” pretends to be a wolf, and the other players pretend that it is hunting them.

Photo by Doug Smith

“The one who is . . . the wolf has now to run after all the others, and every time he catches any one must touch him either on the neck or at the waist up under the tunic, but always on the bare skin; to touch the dress does not count. The moment the wolf touches one of the others he must say: ‘I have touched his skin’ and the one so touched is then wolf in his turn. And so the game goes on until all have been wolf.”

—Rasmussen (1930:245)

“This young woman and her sister and a band of girls went down to the creek. After they got there, her sister proposed that they play a game of bear, one to act as bear and the others to go near the den and pick berries, and the bear would chase them until he caught one of them.”

—Parsons (1929:10)

Similarly, in the Kiowa chase game called setyayum (“Bear Play”), the players imagine that they’re picking berries near a bear’s den, and that the person chasing them is a bear. This game is described in a story about a girl who transforms into a bear while playing this game and tries to kill the other players.

Photo by Ashley Lee

Other chase games reference smaller threats, such as biting and stinging insects. This is seen in a game called “March-fly” played by Aboriginal Australians, in which the person who is “it” pretends to be a fly and runs after the other children trying to “sting” them.

Swarming bees | Photo by Waugsberg

“there is a . . . game in which the performers play the parts of birds or insects. ‘March-fly’ is played by one child taking the part of the fly, shutting his or her eyes and running about to try and catch some one; as soon as success attends their efforts, they buzz in the ear of the captive and pinch him in imitation of the insect’s sting.”

—Thomas (1906:131)

“This game resembles the European ‘puss in the corner,’ and ‘fox and geese.’ A square is drawn in the snow, and in the center stands the person who is ‘it’ (called . . . ‘the cannibal’). The other players occupy the four corners of the square. The object of the game is to run from corner to corner without being touched by ‘the cannibal.’ If ‘the cannibal’ succeeds in touching anyone, that person becomes ‘it’ and takes his place.”

—Skinner (1911:38)

Other imaginative frameworks associated with chase play evoke the threat of human predation. Some of these games reference attacks by hostile or deviant individuals. This is illustrated in the Eastern Cree “Square Game,” in which the playing field consists of a square drawn in the snow. The object of the game is to run from one corner of the square to another without being caught by the person who is “it,” who is pretending to be a cannibal.

Other variants of tag reference attack by enemy groups. This is illustrated in a Coeur d’Alêne game in which players simultaneously attempted to take captives and avoid being captured themselves.

Map by Coeur d’Alene Tribe

“A catching game was in vogue, called ‘making slaves.’ Two goals were marked at opposite ends of the playground. . . . The object was to touch the hands of any person of the opposite side, and then return and reach one’s own goal without being caught by him. The person caught was . . . called a ‘slave’ or ‘captive of war,’ and was conducted over to the enemy lines by the person who caught him. The game continued thus until one side was out. Women often participated in this game.”

—Teit (1930:134)

“The girls on the first side have a stuffed skin of a white tree squirrel, and the others have a stuffed skin of a black tree squirrel. . . . The girls of one side run around the base of a hill in one direction. Those on the other side go around in the other direction. Both girls on a side run along together. One of them carries the ‘baby’ in a blanket. . . . If she runs too fast the squirrel may fall out. One picks up the ‘baby’ if the other loses it. The one who returns to the starting point first with the ‘baby’ wins for her side.”

—Opler (1946:83)

Apache cradle board | Photo by Edward R. Curtis

In some games, the chasing is only implied. For example, Jicarilla Apache girls traditionally played a game called “She Carries the Baby.” The game involved four players, two on each side. The objective was to be the first team to safely carry a stuffed squirrel-skin “baby” around the base of a hill. Jicarilla girls were taught that “they must be light and ready to run if an enemy comes” (Opler 1946:91). Thus, this game appears to simulate a tactic commonly used by forager women and children to evade enemy attack — namely, fleeing to a place of refuge. Due to their limited mobility, babies and toddlers had to be carried, making the task more arduous.

“‘Perhaps an enemy is near. You must be ready to jump up and run. If you make yourself like an old fat lady, when the enemy comes, you will be captured and made a slave. We are not always at peace,’ they tell them.”

—Opler (1946:91)

“The children also have da’thasoldibna, ‘we play old ogre.’ One of them assumes the role of the monster who eats children, kiwa’kwe. Another is their protector, while the devourer tries to catch them as they take refuge, with screams, behind him or her. When a child is caught, the monster makes to devour him by biting his clothes and growling, all of which greatly terrifies the rest.”

—Speck (1940:183)

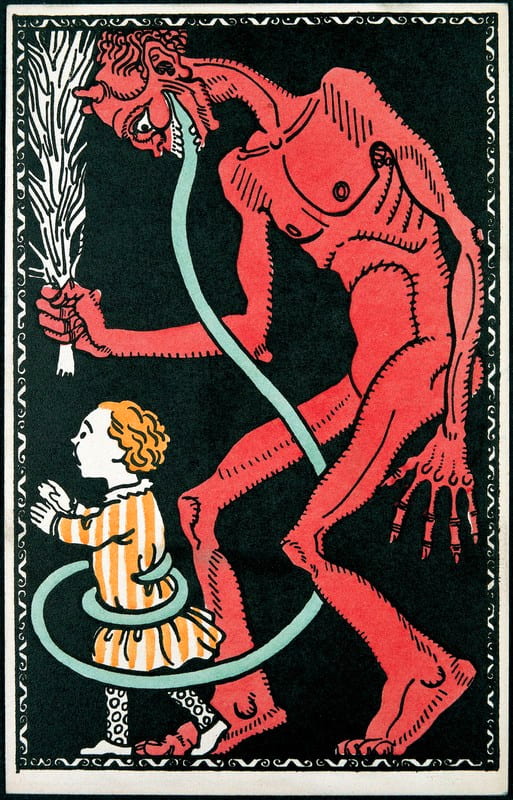

In some variants, the person who is “it” represents a monster. These variants appear to evoke both animal and human attack. This is seen in a Penobscot game, in which the person playing the monster pretends to growl and bite the victim.

Image from Wikimedia

Other imaginative frameworks associated with tag conceptualize the game as a hunt. In the Andaman Islands, for example, mock pig-hunting was popular. In this game, one person runs around in the bush pretending to be a wild pig, while the other players attempt to “tag” him with arrows.

Wild boar (Sus scrofa cristatus) | Photo by JP Bennett

“Mock pig-hunting after dark is another very favourite amusement; one of the party undertakes the role of the pig, and, betaking himself to a distance, runs hither and thither, imitating the grunting of that animal, while his comrades shoot off harmless arrows in the direction from whence the sounds proceed until one hits its intended mark.”

—Man (1883:385)

“Imitating the noise of peccaries by striking together two pieces of wood, boys run after ‘dogs’ or ‘hunters.’”

—Métraux (1946:338)

The Qom people of South America have a similar game in which some players pretend to be peccaries and others pretend to be hunters or hunting dogs.

Peccaries | Photo by Bernard Dupont

Some tag games take place in the water. For example, the Andaman Islanders play at turtle hunting. One person plays the role of the turtle, and the others try to capture him.

Photo by Alexander Vasenin

“Similarly in the sea they play at turtling: one end of a long line is held firmly by some one in the canoe, the other being fastened to the arm of the man who is to represent the turtle. Diving suddenly into the water, he is at once followed by the rest, who try to capture him, while he does his utmost to elude them by swimming, doubling, and diving, till fairly exhausted.”

—Man (1883:385)

“A form of ‘coursing’ is practiced . . . as follows: A wallaby, dingo, rat, etc., having been previously caught with a net, is kept alive and in captivity by means of a strong twine attached to one of its legs. When all the players are ready, and in position, the animal is let go, and must be caught with the hands only, no sticks, stones, or boomerangs being permissible in its recapture.”

—Roth (1897:131)

In other variants of this framework, the quarry is an actual game animal rather than a human pretending to be one. For example, among the Aboriginal peoples of Queensland, Australia, children would capture a small animal, then let it go and chase it until one of them caught it.

Wallaby | Photo from Wikimedia

Hide-and-Seek

Many chase games have a searching component. In this form of tag, one or more players hide, and the player or players who are “it” must find them. In some variants, there is only one seeker, while in others there is only one hider. The Hudson Bay Inuit play a challenging version of the latter, in which the hider is required to change hiding places during the search.

Inuit village | Image from Wikimedia

“One of the players hides, and the others look for him. As soon as the one in hiding is found, all must run after him, and the first to touch him is the next to hide. When one has gone into hiding, the rest cry . . . ‘comrade, utter a sound.’ The one in hiding must then whistle, and should as often as possible change his hiding place and whistle again, so as to deceive the others as to his position.”

—Rasmussen (1930:245)

“Another variety of this game is as follows: one man leaves the encampment after dark armed with ū·tara arrows, which, on his return after a brief absence, he fires off into different huts, while the occupants hide themselves or run away screaming as if attacked by an enemy.”

—Man (1883:385)

Imaginative Frameworks

Imaginative frameworks are also present in hide-and-seek games. Some of these framings evoke the threat of warfare. This is illustrated in a variant from the Andaman Islands in which play simulates enemy attack.

Andamanese fishermen | Photo from Wikimedia

A similar variant, minus the arrow shooting, was played by the Orok (Ul’ta) and Nivhgu people of Sakhalin Island and the lower Amur River.

Nivhgu village | Image from Wikimedia

Nivhgu men and women | Image from Wikimedia

“I observed the Orok and Nivhgu children playing hide-and-seek. They order one or two of them to stay inside a yurt and forbid them to look where the other participants in the play hide. The latter run in all directions outdoors and into neighboring houses and storehouses. When all are well hidden, one of them shouts loudly kuk, and this interjection signifies that . . . those sitting in the yurt can begin their search.”

—Pilsudski (1998:674)

“The children play also blind-man’s-bluff. . . . They blind the eyes of one of the participants with some rag, and all the others try to harass him, striking his hands or back and pulling at his clothes, and he runs after them striving to catch anyone who when caught replaces him and with blinded eyes tries to catch some other child.”

—Pilsudski (1998:674)

In some variants of hide-and-seek, seekers must close their eyes or wear a blindfold (as in “March-fly,” above). In English this game is known as “blind man’s bluff.” Some variants, such as Marco Polo, are played in the water. In a variant played by Orok (Ul’ta) and Nivhgu children, the players are allowed to harass the chaser.

Blind Man’s Bluff | Photo from Wikimedia

References

Aldis, O. (1975). Play Fighting. New York: Academic Press.

Man, E. H. (1883). On the Aboriginal Inhabitants of the Andaman Islands, Part III. Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 12, 327-434.

Métraux, A. (1946). Ethnography of the Chaco. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Opler, M. (1946). Childhood and Youth in Jicarilla Apache Society. Southwest Museum.

Parsons, E. C. (1929). Kiowa Tales. New York: American Folklore Society.

Piłsudski, B. (1998). The Collected Works of Bronisław Piłsudski. Volume 1, The Aborigines of Sakhalin (A. F. Majewicz, Ed.). Mouton de Gruyter.

Rasmussen, K. (1930). Intellectual Culture of the Hudson Bay Eskimos (W. J. A. Worster & W. E. Calvert, Trans.). Gyldendal.

Roth, W. (1897). Ethnological Studies Among the North-west-central Queensland Aborigines. Brisbane: E. Gregory, Government Printer.

Skinner, A. (1911). Notes on the Eastern Cree and Northern Saulteaux. New York: Trustees.

Speck, F. G. (1940). Penobscot Man; the Life History of a Forest Tribe in Maine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Teit, J. A. (1930). The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus (F. Boas, Ed.). Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Thomas, N. W. (1906). Natives of Australia. London: A. Constable & Company.