Learning What to Learn: The Development of Selective Attention

Michelle Scalise Sugiyama | January 21, 2022

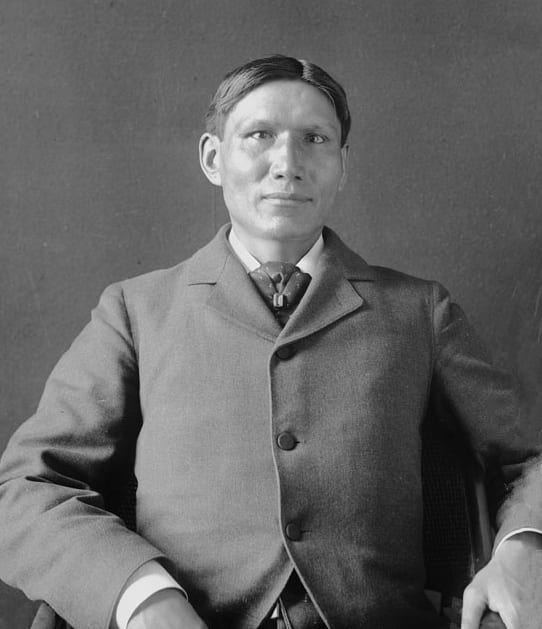

Charles Eastman | Photo by Wells Moses Sawyer

“It is commonly supposed that there is no systematic education of their children among the aborigines of this country. Nothing could be farther from the truth.”

—Eastman (1902:49)

With notable exceptions (e.g., Hilger 1951, 1952; Opler 1946), ethnographers have long contended that little or no formal instruction occurs in forager societies, and that much learning occurs through observation and imitation of others (e.g., Blurton Jones & Konner 1976; Gould 1969). While the latter certainly appears to be the case, it does not follow—as some have concluded (e.g., Lancy 2016; MacDonald 2007)—that teaching is rare or absent among hunter-gatherers. This claim hinges on what is meant by “formal instruction.” If it means the daily herding of children into a dedicated space for several hours of reading, writing, and arithmetic, we can safely say that knowledge transmission in forager societies does not take this form (Geary 2022). However, this is a rather narrow, ethnocentric view of formal instruction, pointing to a glaring omission in this debate: the voices of individuals versed in hunting and gathering.

Defining teaching in terms of post-industrial pedagogical practices is akin to arguing that foragers lack manufacturing because they lack factories: formal instruction may take different forms under different socio-ecological conditions. Clearly, a definition is in order. Lancy characterizes formal instruction as learning “dominated by a top-down transfer of knowledge (teaching) from experts/teachers to novices/pupils” (2016:7). He contrasts this with novice-led knowledge transfer, in which “the eager, self-initiating learner takes advantage of social learning opportunities to replicate (often initially in play) the observed skills and behaviors practiced by members of his/her family and community” (Lancy 2016:7). This dichotomy raises several important questions: (a) Who or what causes social learning opportunities to occur, (b) how do novices recognize them as such, (c) what motivates them to take advantage of these opportunities, and, for a given learning opportunity, (d) how do they determine which actions to imitate and which to ignore?

Who provided the sandbox and the toys?

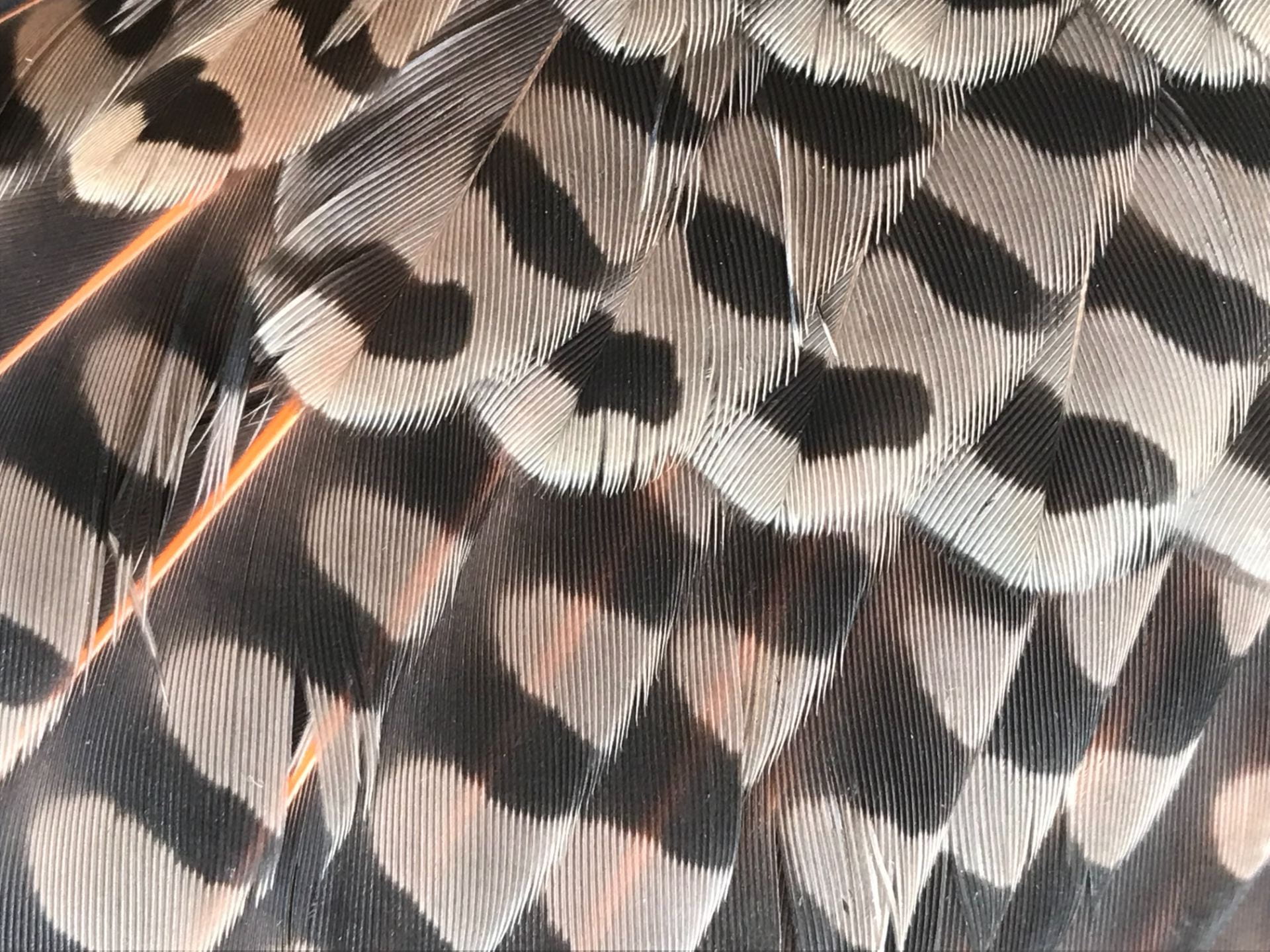

Photo by Artaxerxes

Taxonomies of teaching behavior indicate that observational learning does not occur through osmosis. On the contrary, experts play an instrumental role in novice-driven learning: many social learning opportunities are initiated, guided, and/or encouraged by adults (e.g., Hewlett & Roulette 2016; Kline 2017; Strauss & Ziv 2012). For example, an expert may reposition a tool in a novice’s hand, thereby teaching them how to wield it correctly. Other examples include stimulus enhancement (i.e., directing a novice’s attention toward a learning opportunity), task assignment (e.g., sending a novice to collect firewood), and evaluative feedback (e.g., praising or criticizing the novice’s performance). These behaviors identify a given circumstance as a learning opportunity, guide novices’ attention toward its instructive aspects, and encourage them to pursue it. Indigenous perspectives provide a vivid illustration of this principle, as seen in Eastman’s description of his Dakota childhood training:

“My uncle, who educated me up to the age of fifteen years, was a strict disciplinarian and a good teacher. When I left the teepee in the morning, he would say: ‘Hakadah, look closely to everything you see’; and at evening, on my return, he used often to catechize me for an hour or so. . . . It was his custom to let me name all the new birds that I had seen during the day. I would name them according to the color or the shape or the bill or their song or the appearance and locality of the nest—in fact, anything about the bird that impressed me as characteristic. I made many ridiculous errors. . . . He then usually informed me of the correct name.”

—Eastman (1902:52-53)

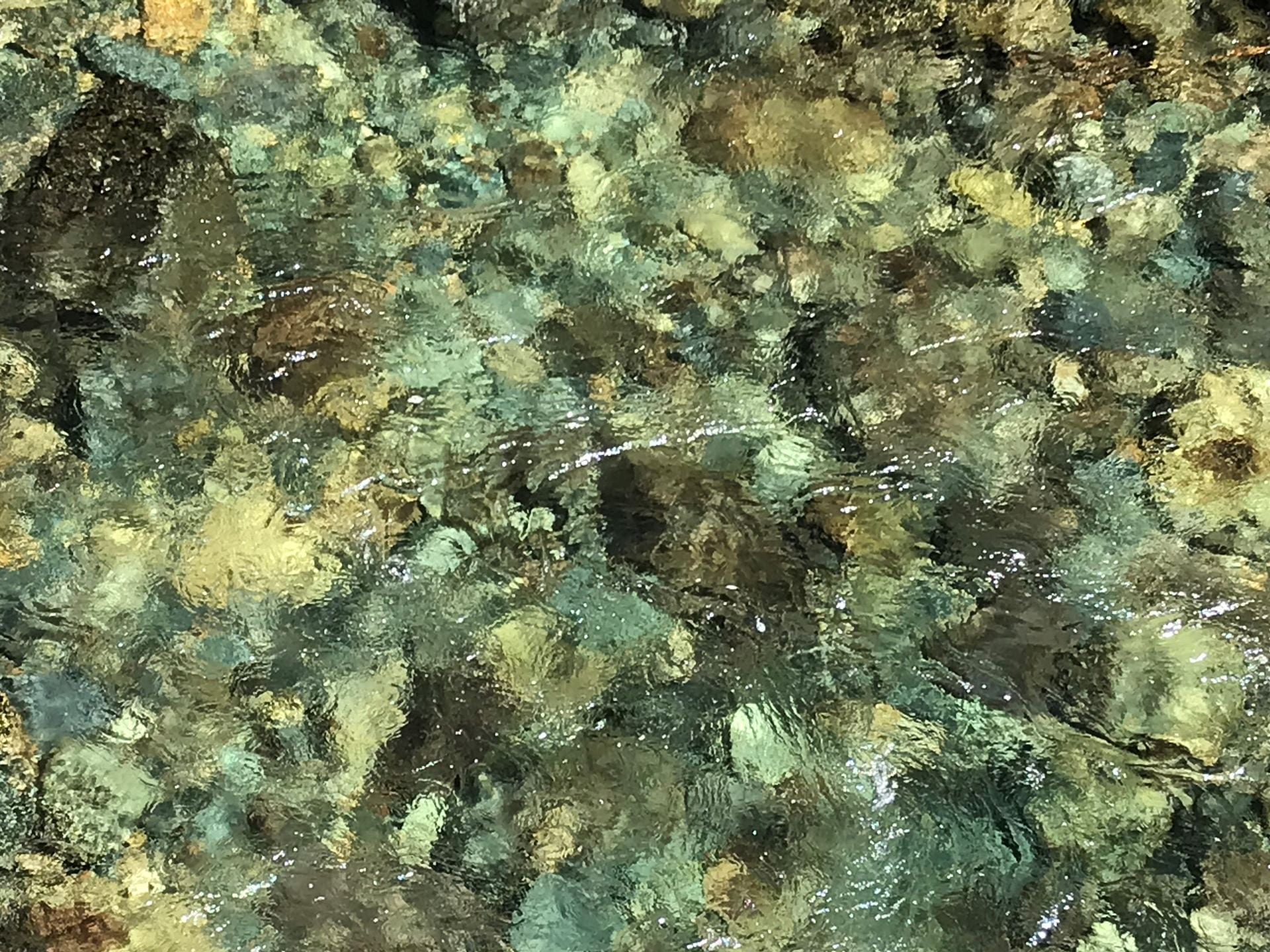

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Osprey Call

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

The exhortation to conduct close observations, followed by a rigorous question-and-answer session, is the equivalent of an assignment followed by an exam—a clear case of an expert intervening to encourage and guide a novice’s observational learning. Nor was this a one-off occurrence; the tests continued and became more challenging in Eastman’s later childhood:

“He went much deeper into this science when I was a little older, that is, about the age of eight or nine years. He would say, for instance: ‘How do you know that there are fish in yonder lake?’ ‘Because they jump out of the water for flies at mid-day.’ He would smile at my prompt but superficial reply. ‘What do you think of the little pebbles grouped together under the shallow water? And what made the pretty curved marks in the sandy bottom and the little sand-banks? Where do you find the fish-eating birds? Have the inlet and the outlet of a lake anything to do with the question?’”

—Eastman (1902:53)

Photo by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Osprey | Photo by Sumeet Moghe

By showing novices what to learn about their environment, promptings by experts support “the development of selective attention” (Mithen 1990:246), a prerequisite to efficient and productive observational learning. In his analysis of Upper Paleolithic cave art, Mithen argues that, in conjunction with song, dance, and myth, these images served to specify “which particular types of animals, and which aspects of their behavior and form, should be attended to if relevant information is to be gathered” (1990:246).

Altamira Cave by Yvon Fruneau

Eastman’s experience suggests that this training began early. When he was just a toddler, his grandmother taught him the calls of different bird species, and their significance:

“After I left my cradle . . . she. . . . began calling my attention to natural objects. Whenever I heard the song of a bird, she would tell me what bird it came from, something after this fashion: ‘Hakadah, listen to Shechoka (the robin) calling his mate. He says he has just found something good to eat.’ Or ‘Listen to Oopehanska (the thrush); he is singing for his little wife. He will sing his best.’ When in the evening the whippoorwill started his song with vim, no further than a stone’s throw from our tent in the woods, she would say to me: ‘Hush! It may be an Ojibway scout!’”

—Eastman (1902:9)

Robin Song

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Robin | Photo by Phil Myers

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Expert-guided learning is not limited to the acquisition of zoological knowledge. Paulus Maggo, a Labrador Inuit hunter and fisherman, describes the hazards of winter travel that his father pointed out to him:

“My father would tell me to watch for and be able to recognize hazardous places and spots on thin ice, whether it was on the sea, lakes, ponds, or rivers. I had to learn to recognize the dangerous features of shale or thin ice, bridged or suspended ice, and possible sink holes in the snow with water underneath. My father told me about all of this and much more. He’d point out to me and show me the telltale signs of potentially dangerous places and spots whenever we came across them during our travels.”

—Maggo & Brice-Bennett (1999:76)

The ethnographic record indicates that experts also guided novices’ imitative learning. This was achieved by indicating which individuals and behaviors they should—or should not–imitate. Among the Chippewa, for example, “A mother would put some food into a dish and tell her child to take it to the neighbors, and so teach the child to give and share” (Hilger 1951:98). Similarly, an Arapaho informant reports: “The two things my father talked to me about especially were not to steal and not to lie. When a young man where we lived would lie, my father would say to me, ‘That man lies. He steals too. Don’t ever do that’” (Hilger 1952:103). The common practice of providing children with miniature tools, weapons (e.g., Lew-Levy 2017; MacDonald 2007) and athletic equipment has the same effect, marking certain activities as important and thereby signaling which skills to emulate. This was also accomplished through ritual. Among the Algonquian peoples of James Bay, for example, the “walking-out” ceremony literally walked toddlers through the role they were expected to play in their community as adults:

“The ceremony for first walking-out was symbolic of success in the food quest. The little boy should walk this first time without faltering directly to where game was to be found as it was hoped he would be able to do in the future. . . . wearing at one hip a small wooden replica of a powder horn attached to a line passing over the opposite shoulder, and on the other hip a small leather pouch containing a little shot. In his pocket was placed a fancy carrying line of appropriate short length and made of plaited caribou hide and he carried a small wooden gun in his hands. Thus equipped as a hunter he stood inside the wigwam among the spectators. Meanwhile, part of whatever ‘big’ game was available . . . had been placed at some distance from the door which was then opened and the child was told to walk in a straight line therefrom. Then he was told: ‘See that wavey (or whatever meat had been placed for him) in the woods? Shoot it!’ The boy aimed and made a noise imitating a shot, ‘killing’ the animal. The meat was then fixed in a pack which the child carried on his back by means of the decorated carrying-line passed over his forehead.”

—Flannery (1962:478)

A similar ceremony was held for girls, with firewood taking the place of game. Other examples indicate that training began in infancy, though the medium of lullabies and other songs. As Eastman explains:

“scarcely was the embryo warrior ushered into the world, when he was met by lullabies that speak of wonderful exploits in hunting and war. . . . He is called the future defender of his people, whose lives may depend upon his courage and skill. If the child is a girl, she is at once addressed as the future mother of a noble race.”

—Eastman (1902:50)

Lullabies, ceremonies, and playthings are not typically regarded as a part of formal education, but have much in common with it: they are age-appropriate, performed or used on a recurrent basis, and characterized by a top-down dynamic. Furthermore, they direct novices’ attention to very specific features of the local environment by encouraging engagement in very specific activities. In so doing, they show children what they need to learn. A gift of a toy bow and arrow, for example, is a broad hint that one is expected to hunt and thus should master its use and study animal behavior. Importantly, the development of selective attention also teaches novices what they can ignore: under conditions of oral transmission, where cumulative cultural knowledge is stored in memory, this strategy may help maximize storage capacity by forfending the input of useless information.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

The intimate familial context in which these activities occur may explain the Western impression that forager societies lack formal education: anthropologists might not recognize them as teachings or might not be present when they take place. Herein lies the problem: it is not the context in which instruction occurs that makes it formal. Formal instruction is an established procedure or set of behaviors for transmitting knowledge. Song, ritual, games, and other periodic, structured forms of cultural expression all meet this criterion, as does a father’s custom of pointing out unsafe ice during winter hunting trips. This practice was clearly aimed at showing Maggo what to attend to and learn, as seen in his account of two men who foolishly attempted to travel over thin ice. It is fitting, then, that he should have the last word on the subject:

“The place where they fell through the ice was the kind of hazard my father used to tell me about. A thin layer of frozen ice, with water below but not touching it, creates an air pocket between the ice and the water beneath it. This is called aKauk and it can form at inlets and outlets of any lake, large or small. It’s visible if you know what to look for.”

—Maggo & Brice-Bennett (1999:84-85)

References

Blurton Jones, N. & Konner, M. (1976). !Kung Knowledge of Animal Behavior. In R. B. Lee & I. DeVore (Eds.), Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers, 325-348. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eastman, C. (1902). Indian Boyhood. New York: McClure, Phillips & Co.

Flannery, R. (1962). Infancy and childhood among the Indians of the east coast of James Bay. Anthropos, 57(3/6), 475-482.

Geary, D. (2022). Sex, mathematics, and the brain: An evolutionary perspective. Developmental Review, 63, 101010.

Gould, R. (1969). Yiwara: Foragers of the Australian Desert. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Hewlett, B. & Roulette, C. (2016). Teaching in hunter-gatherer infancy. Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), 150403.

Hilger, M. (1951). Chippewa Child Life and its Cultural Background. Washington: United States Government Printing Office.

Hilger, M. (1952). Arapaho Child Life and its Cultural Background. Washington: United States Government Printing Office.

Kline, M. (2017). TEACH: An ethogram-based method to observe and record teaching behavior. Field Methods, 29(3), 205-220.

Lancy, D. (2016). Teaching: natural or cultural? In D. Geary & D. Berch (Eds.), Evolutionary Perspectives on Child Development and Education, pp. 33-65. Heidelberg, DE: Springer.

Lew-Levy, S., Reckin, R., Lavi, N., Cristóbal-Azkarate, J., & Ellis-Davies, K. (2017). How do hunter-gatherer children learn subsistence skills? A meta-ethnographic review. Human Nature, 28(4), 367-394.

MacDonald, K. (2007). Cross-cultural comparison of learning in human hunting. Human Nature, 18(4), 386-402.

Maggo, P. & Brice-Bennett, C. (1999). Remembering the Years of My Life: Journeys of a Labrador Inuit Hunter. St. Johns, Newfoundland: Institute of Social and Economic Research, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Mithen, S. (1990). Thoughtful Foragers: A Study of Prehistoric Decision Making. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Opler, M. (1946). Childhood and Youth in Jicarilla Apache Society. Los Angeles: The Southwest Museum.

Strauss, S., & Ziv, M. (2012). Teaching is a natural cognitive ability for humans. Mind, Brain, and Education, 6(4), 186-196.