Evenk Astronomy

Entry by Matthew Hampton & Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

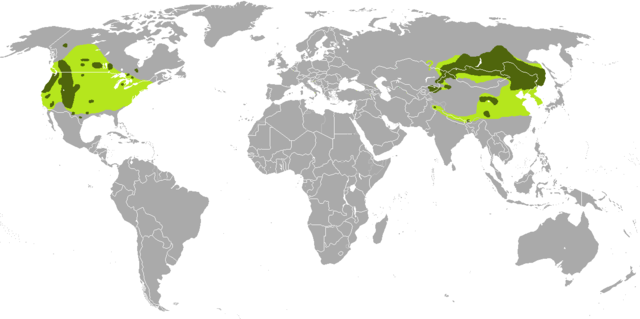

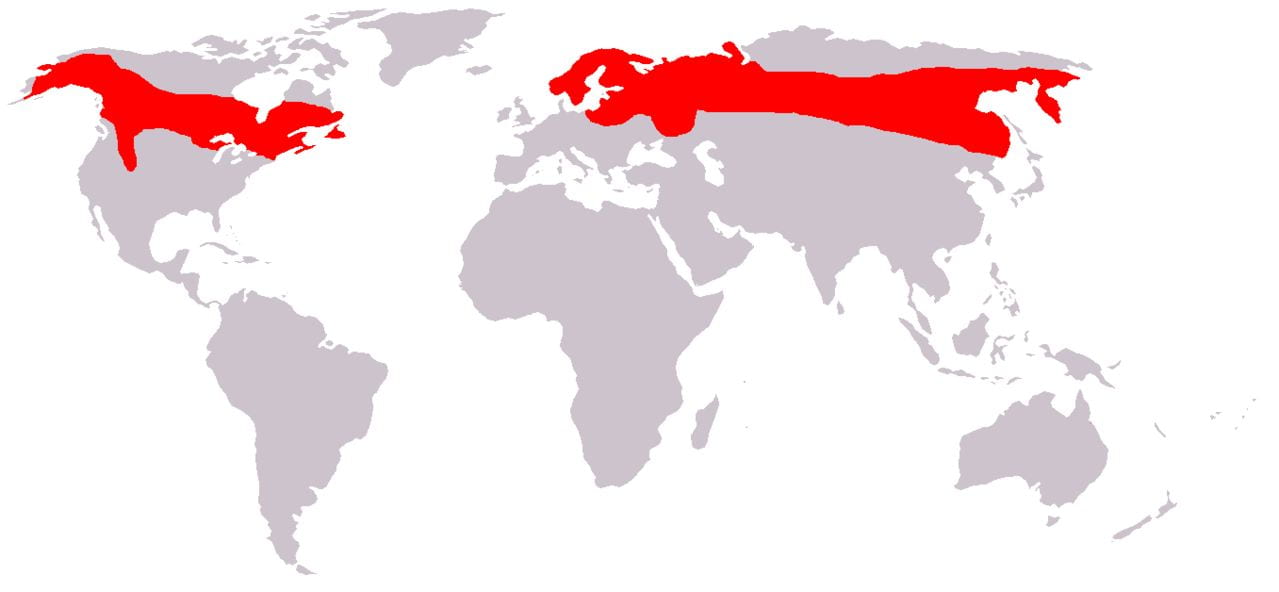

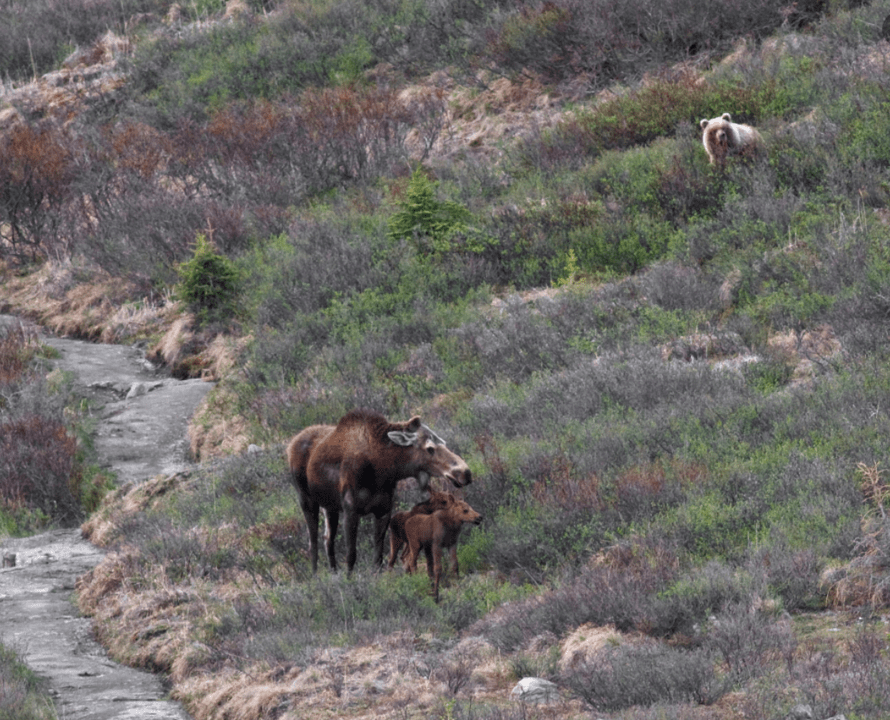

Among the Evenk people, several constellations are associated with hunting. The Pleiades and Orion are conceptualized as three hunters pursuing a mountain sheep (Frank 2015:1683). Similarly, the Big Dipper is seen as a hunter or hunters pursuing an “elk,” called Kheglen or Keglun (Anisimov 1963). The hunters are associated with the stars of the dipper handle, and the animal is associated with the stars of the dipper. It is unclear whether this animal is an elk or a moose, the latter of which are called “elk” in Eurasia. Traditionally, the Evenki occupied a vast swath of the Siberian taiga, from the Yenisey River Basin to the Lake Baikal region. Moose, which are a taiga-adapted species, range throughout Evenk territory, while elk are confined to its more southerly regions. Additionally, elk are a gregarious species, whereas moose are solitary like the animal in the constellation (De Bord 2009; Senseman 2002).

Traditional Evenki territory | Map by Kmusser

Elk range worldwide | Map by Altaileopard

Moose range worldwide | Map by Jürgen Gbruiker

Moose cow and calf | Photo by Phil Myers

There are several variants of the Kheglen myth, some of which incorporate Ursa Minor, the Milky Way, and/or Orion. One variant conceptualizes Kheglen as a female and her calf being chased by three hunters. Ursa Minor is the calf, and the Milky Way represents the tracks made by the hunters’ skis (Anisimov 1963:161-162). Among the western Evenki, the faint star (Alcor) near Mizar (the second star of the dipper handle) is seen as a cooking pot carried by one of the hunters, while the Orochon Evenki envision it as his dog (Berezkin 2005:82-83).

In another variant, Kheglen is male and steals the sun from the sky, causing perpetual darkness. He is pursued across the horizon from east to west by the hero Main, who travels on winged skis. At midnight, Main shoots Kheglen with an arrow and takes back the sun, restoring daylight to the people. In a slightly different version, the stars of the dipper are Kheglen’s hooves (which might be a reference to the animal’s tracks), and the stars of the handle are the hero Main and the arrows released from his bow in the course of the hunt (Anisimov 1963:162-163).

In the oldest version of the myth, the hunter is the ancestral bear-man Mangi, who overtakes Kheglen, kills him, and proceeds to gorge himself. In this variant, the Milky Way is the track made by Mangi’s skis, Ursa Major is Kheglen’s legs, and Orion is his thigh joint. The bear-man Mangi is associated with the stars Boötes and Arcturus (Anisimov 1963:164). This variant may encode information about a moose hunting strategy: since bears hunt moose, listening for their growls and following their spoor might lead you to a fresh moose kill.

The Kheglen myth references seasonal transitions: the theft of the sun occurs at the autumnal equinox, and the killing of Kheglen and restoration of the sun occur at the vernal equinox (Frank 2015:1681-1682). Thus, the myth marks environmental changes that sharply affect subsistence in the far north—the short days of fall and winter and long days of spring and summer. The myth was also associated with spring religious rites, which were performed to ensure renewal of the resources people depended on, as well as future hunting success. Rites lasted several days, and involved acting out the myth. Participants played the part of the hunters, “chasing” their prey until it was overtaken and “killed.” This was done symbolically by shooting arrows into a wooden image of the animal, which was then chopped into pieces and distributed among all the participants (Anisimov 1963:163-164). This part of the ritual appears to encode information about social norms: the Evenk custom of nimat mandated that a hunter share his catch with everyone living in his camp (Vasilevich & Smolyak 1964:645).

Photo by Dmitry Azovtsev

The myth’s reference to large ungulates and (in the Mangi variants) a bear reflects their importance in Evenk subsistence. Reindeer, Eurasian elk (moose), and bear meat provided the bulk of the diet. Hoofed animals also provided raw materials for clothing, shelter, and implements (Vasilevich & Smolyak 1964:625-626).

Photo by Kyle Joly

In the eastern regions of Evenk territory, the mountain ram (associated with the Pleiades and Orion) was also hunted (Vasilevich & Smolyak 1964:636). Fish, too, were important, for both consumption and trade (Vasilevich & Smolyak 1964:631). The Nivkh, who lived to the east of the Evenki, used the summer position of the Milky Way to predict annual fluctuations in fish populations: when it paralleled the course of the Tumen river the fishing would be good, but when it crossed the river the fishing would be bad (Anisimov 1963:219). References to the Milky Way in Kheglen myth variants may encode similar information.

Photo by Steve Jurvetson

“The motif of the cosmic hunt was a form of personification of the sun cycle which corresponded to and reflected the forms of economic activities.”

–Anisimov (1963:164)

The Kheglen myth is an expression of the cosmic hunt motif (Thompson 1955-1958:12). This motif, in which “certain stars and constellations are interpreted as hunters, their dogs, and game animals, killed or pursued” (Berezkin 2005:79), is widespread across forager cultures. In the circumpolar north, the target of the hunt is typically a large species such as moose or bear (Hagar 1900). Among the Micmac of Nova Scotia, the cosmic hunt myth encoded information about bear hunting season (Hagar 1900). The Kheglen myth may encode similar knowledge about moose (or elk) hunting.

The Evenki are not the only foragers who skied: skis have been found among the Samoyed, Chukchi, Lamut, Ainu, and Saami (Weinstock 2005:192). Several lines of evidence suggest that skiing dates back thousands of years. The oldest known ski fragments, found in northern Russia, have been dated to 6300-5000 BCE, while the Kalvträskskidan ski, found in Sweden, dates to 3300 BCE. Linguistic evidence suggests that skiing originated in what is now northern Mongolia, then spread northeast to Siberia and northwest to Fennoscandida (Weinstock 2005:173).

Kalvträskskidan ski | Photo by moralist

Rock carvings depicting people on skis, dated to ~2000 BCE, have been found in Norway and in northwest Russia near the White Sea. Interestingly, the latter site includes a hunting scene that is strikingly similar to the Kheglen myth. The scene depicts three armed humans on skis pursuing three moose, and shows the tracks of the skis and poles. Two of the animals have been pierced by arrows, and the third has been pieced by a spear (Weinstock 2005:178). Similarly, rock carvings at Alta, Norway, dated to ~1000 BCE, depict a skier in the act of shooting a moose with a bow and arrow (Weinstock 2005).

The Evenki also used the stars for navigation. The explorer V. K. Arsenyev notes that his Evenk guide used the heavens to plot a course across the flat tundra: “every evening the guide observed the stars and learned from them whether or not the party was following the right way and what direction was to be kept” (Anisimov 1963:220).

“Evenks can calculate precisely and explain where and on what side he should ‘hold’ [observe] the heavenly bodies (the sun, the stars) at various times of day and night in order to come to the appointed place.”

–Anisimov (1963:220)

Siberian tundra | Photo by Dr. Andreas Hugentobler

References

Anisimov, A. F. (1963). Cosmological concepts of the peoples of the north. In H. Michael (Ed.), Studies in Siberian Shamanism., 157-229. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Berezkin, Y. (2005). The cosmic hunt: Variants of Siberian-North American myth. Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore, 31, 79-100.

De Bord, D. (2009). “Alces alces” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 13, 2022 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Alces_alces/

Frank, Roslyn, M. (2015). Skylore of the Indigenous peoples of northern Eurasia. In C. Ruggles (Ed.), Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, 1679-1686. New York: Springer.

Hagar, S. (1900). The celestial bear. Journal of American Folklore, 13(49), 92-103.

Senseman, R. (2002). “Cervus elaphus” (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 13, 2022 at https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Cervus_elaphus/

Thompson, S. (1955–1958). Motif-Index of Folk Literature. A Classification of Narrative Elements in Folktales, Ballads, Myths, Fables, Medieval Romances, Exempla, Fabliaux, Jest-Books and Local Legends, Vol. 3. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Vasilevich, G. M. & Smolyak, A. V. (1964). The Evenks. In M. G. Levin & L. P. Potapov (Eds.), The Peoples of Siberia, 620-654. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Weinstock, J. (2005). The role of skis and skiing in the settlement of early Scandinavia. The Northern Review, 25/26, 172-196.