The Logistics of Cultural Transmission

Michelle Scalise Sugiyama | February 2, 2021

“to draw inferences regarding symbolic understandings of animals depicted in carvings and other ‘art,’ it is critical to first document the complex real-world relationships among animals, humans, and their environment”

–Betts et al. (2015:92)

As a species, humans are characterized by cumulative culture: the ability to transmit, store, and thereby conserve knowledge from generation to generation. The emergence of cumulative culture is rooted in aural, visual, tactile, and kinetic modes of transmission: the overwhelming majority of cultural transmission has been conducted in the absence of writing and permanent settlements—that is, with little in the way of external memory systems. These conditions sharply constrained the available options for storing and disseminating information. The immense volume of knowledge needed to make a living by foraging thus posed a daunting information management problem for ancestral humans: local knowledge had to be encoded, stored, organized, cross-referenced, refreshed, retrieved, and disseminated using means that were efficient and handy. This problem begs an important question: What media did our ancestors use to store and disseminate their accumulated knowledge? In this essay, I present evidence that the path to this answer begins with pan-human forms of cultural expression, such as storytelling, visual art, song, dance, and games.

Understanding the constraints on information storage and dissemination imposed by hunter-gatherer life is key to understanding the logistics of cultural transmission—that is, to identifying the cultural institutions that subserve the task of teaching and learning in foraging societies. It is important here to distinguish between teaching capacities and teaching media: the former are most likely adaptations, while the latter are human inventions. Over the past three decades, several cognitive capacities have been identified that appear to scaffold knowledge acquisition and transmission in humans, such as evaluative feedback, stimulus enhancement, and opportunity provisioning (e.g., Byrne 1995; Hewlett & Roulette 2016; Kline 2015; Laland 2004; Strauss & Ziv 2012). Collectively, these capacities provide the foundation for a taxonomy of teaching behaviors; teasing and warning, for example, are different kinds of evaluative feedback (Kline 2017).

Missing from this picture, however, is a corresponding taxonomy of cultural inventions that effect knowledge transmission. Teasing is a case in point: many forager societies practice the joking relationship, whereby a person is allowed or even expected to ridicule certain kin (commonly cross-cousins) when they engage in proscribed behavior. The Ju/’hoansi practice of “insulting the meat” took this a step further, using teasing proactively: when a young man made a large kill, his fellow group members would disparage his achievement to teach him to control his pride and anger, and instill the ethos that no one was entitled to more than anyone else (Lee 2018). The institution of the joking relationship can be seen as a human invention that emerged from the evolved capacity for evaluative feedback.

Iñupiat drummers | Photo by Floyd Davidson

Corroboree dancers | Photo from Wikimedia

Men’s turtleshell rattle | Photo by Uyvsdi

The constraints imposed by non-written cultural transmission cast many pan-human “recreational” or “non-utilitarian” symbolic behaviors (e.g., joking, storytelling, visual art, music, dance, ritual, games) in a practical light. From a life history perspective, the time and energy invested in these activities suggests that they confer an advantage of some sort, and much ink has been spilled over whether they are adaptations or by-products. A variety of benefits have been proposed, which can be roughly divided into cooperation-promoting (e.g., Coe 2003; Dissanayake 1995) and signaling functions (e.g., Apostolou 2015; Hagen & Bryant 2003; Kohn & Mithen 1999; Miller 2000). However, with a few exceptions (Mithen 1990; Pfeiffer 1982; Scalise Sugyama et al. 2020; Tooby & Cosmides 2001), comparatively little attention has been paid to these behaviors as possible solutions to problems posed by cultural transmission in ancestral environments.

As any good general knows, battles are won and lost on logistics. The maintenance of cultural repertoires depends not only on cognitive adaptations that enable social learning, but also on “developmental niche construction”—that is, the creation and maintenance of suitable learning environments (Sterelny 2011). On this view, “leisure” activities such as storytelling, dance, and games can be seen as behaviors that provide developmental milieu tailored to local knowledge and skill demands. These activities create regular opportunities for individuals to interact with their environment in ways that support skill and knowledge entrainment.

Bone flute ~43,000 BP | Photo by dalbera

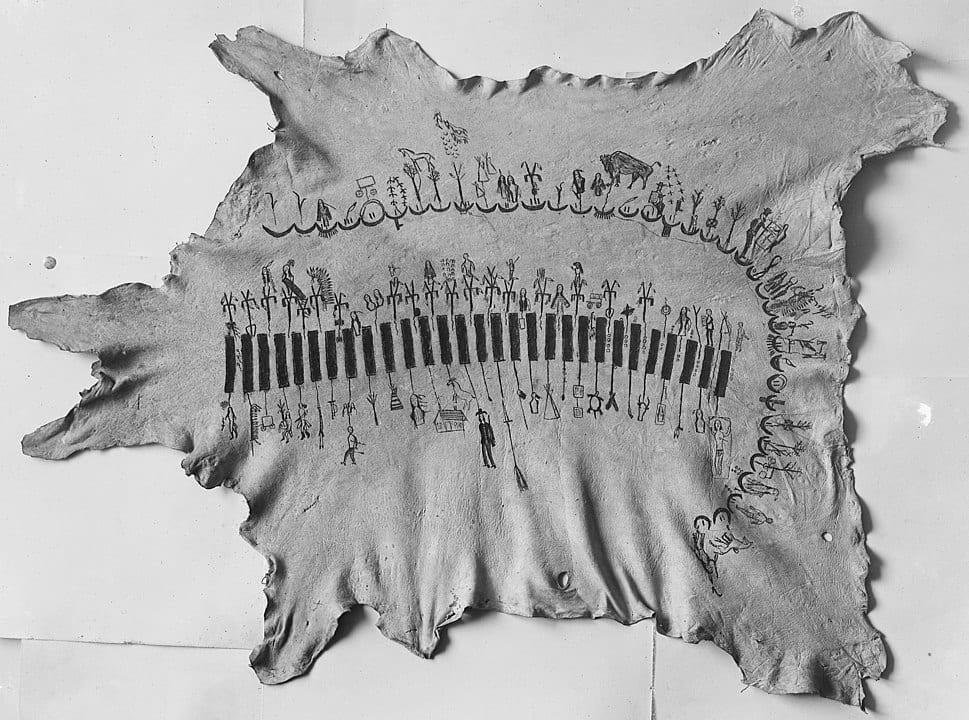

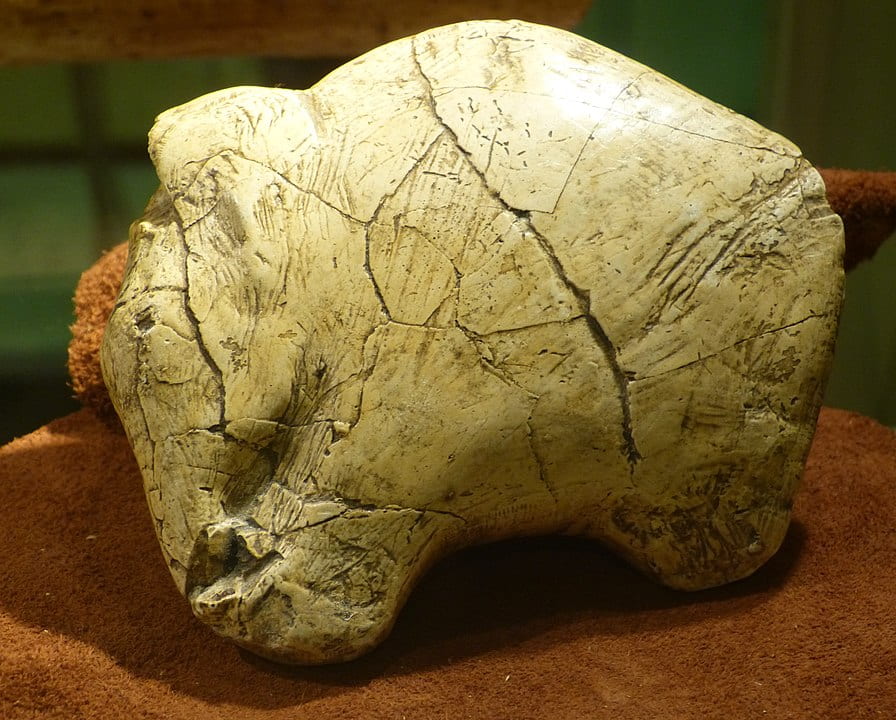

Significantly, the imaginative frameworks that structure these behaviors directly reference the local environment. Strehlow’s observation with regard to the Aranda is true of many hunting-and-gathering peoples: “all legends—and hence all ceremonies, since the latter are always dramatizations of portions of the legends—are tied down to local centres in each group” (1947:1; see also Basso 1996). The ethnographic, ethnolinguistic, and archaeological records all attest to the presence of pronounced patterns in the content (e.g., themes, motifs, referents) of symbolic behaviors across forager cultures, many of which map onto domains of vital ecological knowledge (Scalise Sugiyama 2011, 2017; Turner 2014). For example, much of European Upper Paleolithic art depicts animals that were important in the local economy. Mithen (1990) presents compelling evidence that these images and the geometric marks associated with them depict ecological cues used for locating, tracking, and hunting game.

Chukchi engraving depicting polar bear hunting walrus | Photo by Eliezg

Similarly, the polar bear carvings made by the Dorset people frequently depict this animal engaging in behaviors used to hunt seals at the ice edge, such as diving, swimming, and aquatic stalking. These statuettes “depict those parts of the polar bear that are the most lethal and which interacted with seals in much the same way as Dorset harpoons. Further, the diving behavior of bears physically mimics the motion of a harpoon as it is thrust toward a seal” (Betts et al. 2015:101). Other carvings appear to depict juveniles or pregnant females vocalizing, and may encode information useful for interpreting threat behavior. Betts and colleagues argue that these statues encode an “ethology of polar bears” that was used to transmit and refresh knowledge of local seal hunting practices. Nelson documented the study of polar bear seal-hunting tactics among modern Inuit hunters:

“Sakiak inspected the tracks. . . . The bear had hunted at this allu [breathing hole] and, like him, had found success. It first dug around the dome until the ice was very thin. Then it filled the excavated area with snow scraped from the ice, so the seal could detect no change as it came up inside. Finishing this, it stood beside the allu at a right angle to the wind, awaiting the seal’s return. Eventually, perhaps many hours later, the bear heard its prey breathing within the dome. In an instant it smashed the surrounding ice with both paws, simultaneously crushing the animal’s skull. Then it pulled the seal out onto the ice, squeezing it through a hole so small that many bones broke inside the lifeless body. So it was that . . . [Inuit] and polar bear hunted the same animal in almost the same way.”

—Nelson (1980:21-22)

Songs, too, are widely used to encapsulate zoological information. For example, a children’s song from western Arnhem Land references the blue-tongue lizard’s feeding habits and, by implication, its habitat: “Mushrooms I’m always eating/Mushrooms I eat till I’m full/And where am I going to find them?/Where they are spread about for me/That’s where I’ll find them” (Berndt & Yunupingu 1979:91). Children were taught these songs by adults, who believed that “the songs help children to learn and remember the habits of various creatures—where to find them, what kinds of food they like, what sort of noises they make” (Berndt & Yunupingu 1979:90).

Animals are also a common theme in myths, which encode a wealth of practical zoological information (Scalise Sugiyama 2019). In a Chemehuevi myth, for example, Coyote names all the game animals “larger than a woodrat and illustrates the methods by which they are to be hunted and killed” (Laird 1975:23). Another Chemehuevi myth identifies the body parts of a deer (which narrators were required to enumerate in a certain order), as well as three important watering places (again, in their proper order), and all of the equipment necessary for hunting (Laird 1975:22).

Photo by Christopher Bruno

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

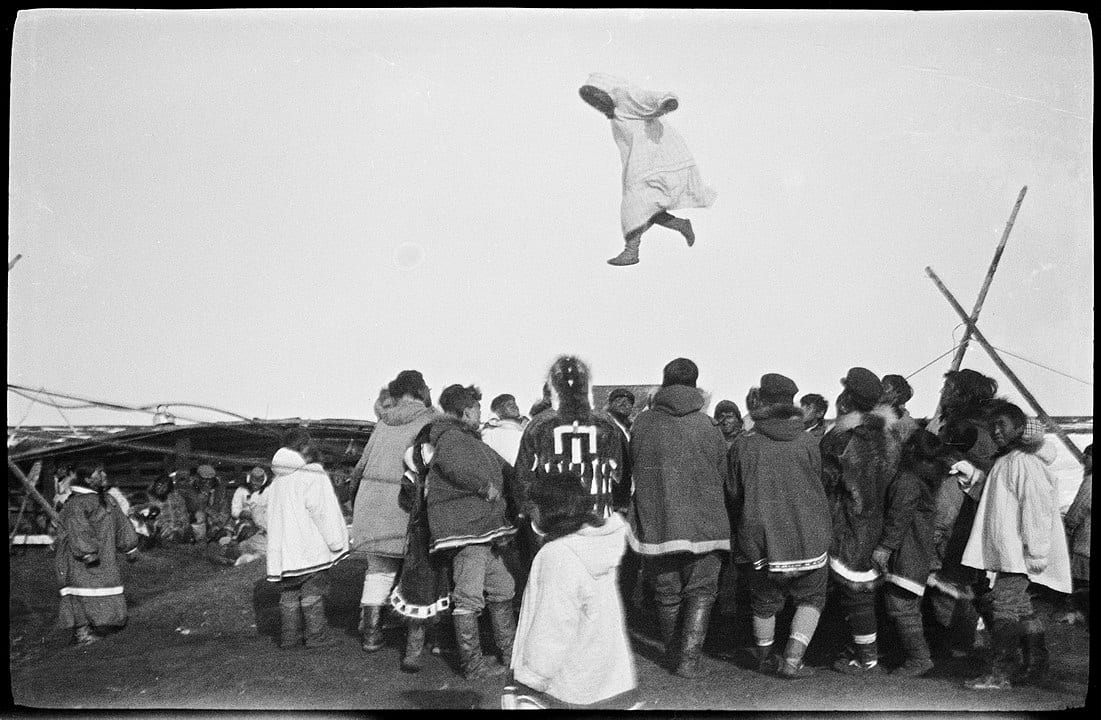

Ecological knowledge is also transmitted through animal mimicry, which is common in storytelling (Scalise Sugiyama 2021), ritual, and dance. In Aboriginal Australia, mimetic dances were an important part of corroborees and ceremonies. Gould describes a ritual in which dancers imitated the evasive tactics of the echidna, which defends itself by “digging into the ground in a series of jerky movements which always leave its quills facing upward for protection” (1969:113). Similarly, Jochelson describes a dance that mimicked the mating behavior of a swan species hunted by the Yukaghir: the male dancer “circles around the female, lifting alternately the left then the right wing (that is, arm); while the female tries to evade his approaches. At the same time the dancing couple imitate the sounds by which the male and the female swans call each other in the pairing-season” (1926:130).

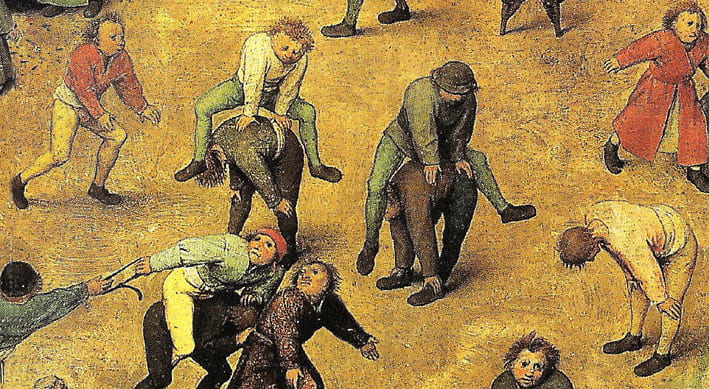

Mimicry also features prominently in play. For example, the Yaghan played a set of games in which the behavior and vocalizations of local species (e.g., sea lion, blue whale, false killer whale, kite, hawk, gerfalcon, albatross, gull, Molinas goose, Magellan goose, oyster catcher, Vigua cormorant) were imitated with great accuracy and detail (Gusinde 1937:1423-1428). In Australia, forager children played games in which “the object is to imitate the movements of some bird or quadruped with the arms or hands” (Thomas 1906:130). They also entertained themselves by drawing animal tracks in the dirt or sand (Roth 1897:131; Thomas 1906:130). Many games simulate predator-evasion scenarios. The wolf game, variants of which are found across Inuit societies (e.g., Rasmussen 1930, 1931, 1932), is a case in point. In this game, one or more players are wolves, and the rest are humans (or in some cases caribou) attempting to escape the wolves. In South America, the “jaguar” game is popular. In this game, players line up behind one another and another player “endeavors to seize or tag the last child of the line, while the group and its leader try to ward him off” (Cooper 1949:505).

Inuit drum dance | Photo from Wikimedia

Mammoth sculpture ~26,000 BP | Photo by Wolfgang Sauber

Chauvet Cave | Photo by HTO

The examples enumerated herein indicate that there are more things in heaven and earth than are currently dreamt of in the study of teaching and learning in hunter-gatherer societies. We need to think more expansively about evaluative feedback, stimulus enhancement, and opportunity provisioning. Teaching is defined as the modification of behavior by an expert in the presence of a novice, such that the expert incurs a cost (or derives no immediate benefit) and the novice benefits by acquiring skills or knowledge it would not acquire otherwise or would acquire less efficiently (Caro & Hauser 1992). By this definition, many of the leisure activities that hunter-gatherers engage in appear to qualify as teaching. “Leisure” is the operative word here: our species’ prolonged childhood and extended period of parental provisioning provide juveniles with surplus time and energy that can be allocated to learning (Lancaster & Lancaster 1983). Thus, to understand how teaching and learning take place among hunter-gatherer peoples, we need to look at how they spend their leisure time: when viewed through the lens of local subsistence practices, many of their “recreational” forms of symbolic behavior are revealed as rich repositories of local ecological knowledge.

Updated January 25, 2022

References

Apostolou, M. (2015). The athlete and the spectator inside the man: A cross-cultural investigation of the evolutionary origins of athletic behavior. Cross-Cultural Research 49(2), 151-173.

Basso, K. (1996). Wisdom sits in places: Landscape and language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Berndt, C. & Yunupingu, D. (1979). Land of the Rainbow Snake: Aboriginal children’s stories and songs from western Arnhem Land. Sydney: Collins.

Betts, M., Hardenberg, M., & Stirling, I. (2015). How animals create human history: Relational ecology and the Dorset-polar bear connection. American Antiquity, 80(1), 89-112.

Byrne, R. (1995). The thinking ape: Evolutionary origins of intelligence. New York: Oxford University Press.

Caro, R. & Hauser, M. (1992). Is there teaching in non-human animals? Quarterly Review of Biology, 67(2), 151-174.

Coe, K. (2003). The ancestress hypothesis. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Cooper, J. (1949). Games and gambling. In J. Steward (Ed.), Handbook of South American Indians, Vol. 5. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 503-524.

Dissanayake, E. (1995). Chimera, spandrel, or adaptation: Conceptualizing art in human evolution. Human Nature, 6(2), 99-117.

Gould, R. (1969). Yiwara: foragers of the Australian desert. New York: Scribners.

Gusinde, M. & Schütze, F. (1937). The Yaghan: The life and thought of the water nomads of Cape Horn. In Die Feuerland-Indianer [The Fuegian Indians], Vol. II. Retrieved from https://ehrafworldcultures-yale-edu.libproxy.uoregon.edu/document?id=sh06-001

Hagen, E. & Bryant, G. (2003). Music and dance as a coalition signaling system. Human Nature 14, 21-51.

Hewlett, B. & Roulette, C. (2016). Teaching in hunter–gatherer infancy. Royal Society Open Science, 3(1), 150403.

Jochelson, W. (1926). The Yukaghir and the Yukaghirized Tungus. Publications of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. 9, Parts 1-3. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Kline, M. (2015). How to learn about teaching: An evolutionary framework for the study of teaching behavior in humans and other animals. Behavioral and Brain sciences, 38, 1-71.

Kline, M. (2017). Teach: An ethogram-based method to observe and record teaching behavior. Field Methods, 29(3), 205-220.

Laird, C. (1975). Two Chemehuevi teaching myths. The Journal of California Anthropology, 2(1), 18-24.

Laland, K. (2004). Social learning strategies. Animal Learning & Behavior, 32(1), 4-14.

Lancaster, J. & Lancaster, C. (1983). Parental investment: the hominid adaptation. In D. Ortner (Ed.), How humans adapt: A biocultural odyssey. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 33-56.

Lee, R. (1984). The Dobe Ju/’hoansi. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Kohn, M. & Mithen, S. (1999). Handaxes: Products of sexual selection? (Stone Age archaeology). Antiquity, 73(281), 518-526.

Miller, G. (2000). The mating mind : How sexual choice shaped the evolution of human nature. New York: Doubleday.

Mithen, S. (1990). Thoughtful foragers. Cambridge, GBR: Cambridge University Press.

Pfeiffer, J. (1982). The creative explosion: An inquiry into the origins of art and religion. New York: Harper & Row.

Rasmussen, K. (1930). Intellectual culture of the Hudson Bay Eskimos, Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 1. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Rasmussen, K. (1931). The Netsilik Eskimos: Social life and spiritual culture, Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 8. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Rasmussen, K. (1932). Intellectual culture of the Copper Eskimos. Fifth Thule Expedition, 1921-1924, Vol. 9. Copenhagen: Gylendal.

Roth, W. (1897). Ethnological studies among the north-west central Queensland Aborigines. Brisbane: Edmund Gregory.

Scalise Sugiyama, M. (2011). The forager oral tradition and the evolution of prolonged juvenility. Frontiers in Evolutionary Psychology, 23 August.

Scalise Sugiyama, M. (2017). Oral storytelling as evidence of pedagogy in forager societies. Frontiers in Cultural Psychology, 29 March.

Scalise Sugiyama, M. (2019). “Etiological animal tales as a typological universal.” Literary Universals Project, University of Connecticut.

Scalise Sugiyama, M. (2021). Co‐occurrence of ostensive communication and generalizable knowledge in forager storytelling: cross-cultural evidence of teaching in forager societies. Human Nature, 32(1), 279-300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-021-09385-w

Scalise Sugiyama, M., Mendoza, M. & Sugiyama, L. (2020). War games: Intergroup coalitional playfighting as a means of comparative coalition formidability assessment. Special issue of Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences on “Sports, Games, and Athletics in Evolutionary Perspective,” R. Deaner & A. Gallup (Eds.). Advance online publication.

Sterelny, K. (2011). From hominins to humans: How sapiens became behaviourally modern. Philosophical Transactions. Biological Sciences, 366(1566), 809-822.

Strauss, S. & Ziv, M. (2012). Teaching is a natural cognitive ability for humans. Mind, Brain, and Education, 6(4), 186-196.

Strehlow, T. G. H. (1947). Aranda traditions. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Thomas, N. (1906). Natives of Australia. London: Archibald Constable and Company, LTD.

Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. (2001). Does beauty build adapted minds? Toward an evolutionary theory of aesthetics, fiction and the arts. SubStance, 30(1/2), 6-27.

Turner, N. (2014). Ancient pathways, ancestral knowledge : Ethnobotany and ecological wisdom of Indigenous peoples of northwestern North America. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.