Cumulative Culture: The Fidelity Problem

Michelle Scalise Sugiyama | January 2, 2024

For most of our species’ existence, knowledge has been stored in memory and transmitted orally. This posed a major obstacle to the emergence of cumulative culture. This term refers to the use of social learning (a.k.a., teaching) to maintain communal knowledge bases over time, and the development of refinements and innovations based on that knowledge. In the hunter-gatherer economies that characterized most of human evolution, knowledge sharing exponentially increased opportunities for innovation by furnishing individuals with information they could not possibly acquire in their lifetime through personal experience alone. The addition of these new discoveries and innovations expanded the existing knowledge base, further necessitating the use of social learning. Over time, this process led to the development of sophisticated technologies, such as the toggling harpoon and kayak, that enabled human populations to expand into novel, inhospitable environments.

Photo from Wikimedia

The emergence and maintenance of cumulative culture depends on the faithful copying of communal knowledge from generation to generation. This raises an important question: In ancestral human cultures, what means were used to prevent information corruption and loss? The ethnographic and ethnolinguistic records suggest that myth was instrumental in the transmission of generalizable knowledge—information that can be used repeatedly, such as how to make fire, track game, or identify medicinal plants. Modern hunter-gatherers often characterize their narrative traditions as teachings, and Western scholarship has shown that these stories encode precise, nuanced, empirical observations of the natural world.

“They used to teach us with stories. . . . Those days they told stories mouth to mouth. That’s how they educate people.”

–Tagish Elder Angela Sidney (Cruikshank 1990:73)

However, storytelling substitutes one memorization task for another: if a myth is misremembered, the generalizable knowledge it encodes faces the same fate. Thus, the effectiveness of storytelling as an information management system hinges on the production of high-fidelity copies from telling to telling, returning us to the question of how this is accomplished.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Research on the formal properties of oral narrative–both prose and verse–shows that these traditions are maintained through the application of multiple mnemonic strategies. Formal and genre constraints further facilitate recall by limiting the performer’s options as a tale or poem is being unraveled from memory. To take a modern example, the coarse subject matter, humorous tone, laconic style, distinctive meter, and AABBA rhyme scheme of limerick sharply delimit the sentiment, syllables, and words that can follow the line, “There once was a man from Nantucket.”

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Maintenance may also be aided by the exploitation of cognitive biases; however, research suggests that this strategy does not guarantee full retention. A series of four experiments using folk stories found that subjects recalled minimally counterintuitive items better than mundane items in the stories. If these findings are representative of oral story transmission in general, we would expect “mundane” content (i.e., practical knowledge) to be lost over time, but this prediction is belied by the plethora of empirical information encoded in forager narrative. For example, a Nez Perce man reports that he remembered which types of wood to use for making a fire drill based on a myth in which Beaver steals fire and puts it into certain tree species, such as willow and birch.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

An ethnographic description of traditional Klamath and Modoc storytelling practices suggests that, among foraging peoples, myths and the knowledge they encode were preserved through the establishment and enforcement of myth-telling rules:

“myth narration occurred principally on winter nights and informal sanctions prohibited myth narration at other times. For example, the Modoc believed that telling myths during the day would cause one to be bitten by a rattlesnake. . . . Klamath myth narration ideally ceased at the end of winter. . . . telling myths after this time would purportedly delay the long-awaited arrival of spring. . . . Only adults were permitted to narrate. . . . However, participation as a listener was unrestricted and generally included the entire winter household. . . . Myths preferably were not mixed with other oral tradition forms. . . . Narrators were not permitted to deviate greatly from local versions. If narrators diverged excessively, listeners would interrupt and engage in debate until the correct version was decided upon.”

—Sobel & Bettles (2000:306-307)

These restrictions limit myth narration to winter nights, when people are confined indoors due to inclement weather and have abundant leisure time. As a result, myth narration takes place when large numbers of people are gathered together, which enables narratives to be “copied” to several minds simultaneously. Moreover, because they are not distracted by more pressing tasks, listeners can give their full attention to the story. Adult-only narration increases the probability that myths are told by persons who know them thoroughly and perform them skillfully. Mixed-age audience composition does double duty: it ensures that older generations are present to check for accuracy and make corrections, and that younger generations are present to learn the myths and carry them into the future. Segregating myth recitation from other types of story performances serves to demarcate the set of texts that are considered essential knowledge, and reduces the chances that their content will be corrupted by admixture with other forms. Lastly, fear of negative sanctions discourages people from breaking these rules. Collectively, these restrictions increase the chances that myths—and the knowledge they encode–are copied correctly to the next generation.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

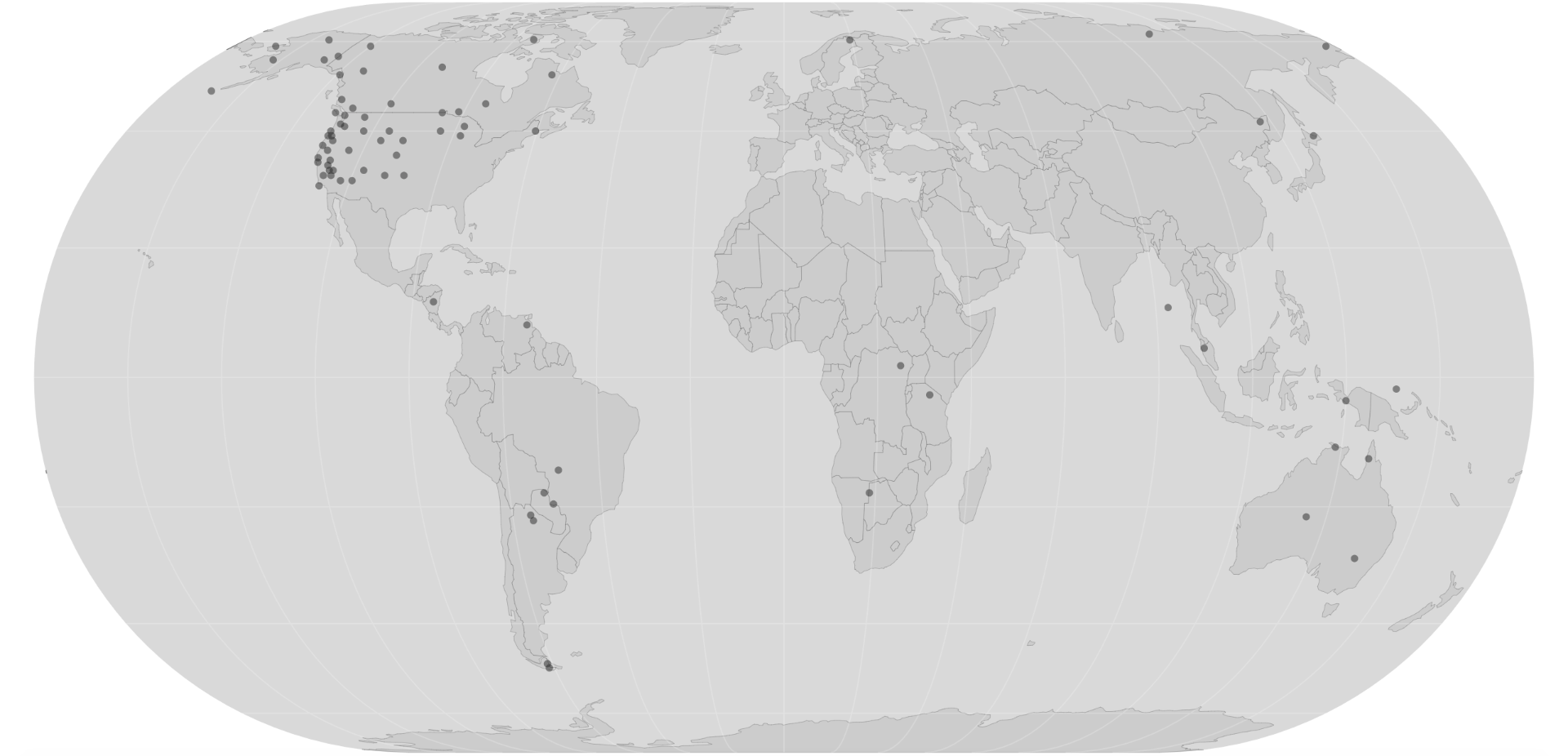

If myths were indeed an important means of transmitting essential communal knowledge, we would expect performance rules like those of the Klamath and Modoc to be common across forager cultures. To investigate this, I searched the forager ethnographic record for descriptions of oral storytelling, which my co-investigator and I then analyzed for the presence of eight rule types: (1) transmission by the most proficient storytellers (2) under low-distraction conditions with (3) multiple individuals and (4) generations in attendance, and the application of measures that (5) prevent, identify, and/or correct mistakes, (6) maintain audience attention, (7) negatively sanction rule violations and/or (8) incentivize rule compliance. Although our sample was heavily biased toward North American foragers, we found descriptions for 80 different cultures, distributed across six continents and diverse biomes.

Map by Kieran J. Reilly

Our findings indicate that myth-telling rules occur across a diverse range of forager cultures. All of the predicted rule types were present on at least three continents, and seven types were present on at least four. Myth recitation was largely the prerogative of older adults and preferentially occurred during periods of low economic activity. Most tellings occurred in the context of formal or informal social gatherings, with mixed-age audiences the norm. Rules regulating narrator performance occurred in 50 cultures, and included the use of prompting (e.g., call-and-response), repetition, song, and other forms of ostensive communication to engage and sustain audience attention. Listeners, in turn, were commonly expected to signal periodically that they were still awake, and to interrupt and correct the narrator if mistakes were made. Evidence of sanctions was limited to Africa and the Americas, and consisted largely of a belief that misfortune would follow rule transgressions:

“When we tell stories, we should not tell only part of a story, they . . . used to say. We have to finish telling it because if we take a long time to tell a story, then the winter will be long. And when the winter is long, people have a hard time.”

—Attla (1983:3)

These findings point to additional factors at play in the emergence of cumulative culture. Symbolic behaviors (e.g., myth, song, dance, visual art, games, names) and rules surrounding their performance have been largely unexplored as systems that support high-fidelity encoding, transmission, and acquisition of generalizable knowledge and skill sets. Re-conceptualizing these behaviors as information technologies may help us better understand how evolved cognitive capacities, ecological constraints, and human inventions interact to produce the ratchets that make cumulative culture possible.

Photo by Michelle Scalise Sugiyama

Attla, C. (1983). As My Grandfather Told It: Traditional Stories from the Koyukuk. Fairbanks: Yukon-Koyukuk School District and Alaska Native Language Center.

Cruikshank, J. (1990). Life Lived Like a Story. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Sobel, E. & Bettles, G. (2000). Winter hunger, winter myths: Subsistence risk and mythology among the Klamath and Modoc. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 19(3), 276-316.